Foreign exchange is a signifier of a country’s wellbeing and can reflect nervousness in economies

by Paul Golden

Even though there are other factors that contribute to the strength of a country’s currency, the perception of foreign exchange rates as a barometer of economic health remains strong.

Huge volumes of currency are traded every day. The Bank for International Settlements’ (BIS) triennial survey (which gathers data from central banks in more than 50 jurisdictions) in April 2019 finds daily trading in FX markets standing at US$6.6tn, having risen from US$5.1tn in the preceding three years.

The market for corporate FX trading is particularly competitive. Global banks such as Citi, JP Morgan and HSBC are the biggest players, according to a recent Greenwich Associates report summary, although proprietary trading firms are emerging as an alternative source of liquidity.

Greenwich Associates managing director Frank Feenstra suggests in the report that smaller and/or regional banks can compete in specific currency pairs where they have a natural advantage and also in specific client segments where they provide credit.

Basic economic theory dictates that strong economies should have strong currencies since they will attract higher capital flows. Meera Chandan, JP Morgan’s global FX strategist, suggests that revisions to the growth outlook can be a meaningful driver of currency returns over the long term, with currencies where growth is upgraded outperforming currencies where growth is downgraded.

But this is not always the case, explains Adam Button, chief currency analyst at FX trading information service provider ForexLive. “Notable exceptions are when inflation gets out of hand and central bankers lose the ability to control it, when the market loses confidence in current account deficits or when political risk becomes too high,” he says.

The US dollar tends to do best when the situation is good or bad and sags in a middling economyIt is important to note that currencies are traded in pairs (such as USD/EUR) so the exchange rate is effectively a direct comparison between two currencies. This means that traders are not just making a call on the attractiveness of the US dollar in the case of the USD/EUR pair – they are also assessing the perceived strength or weakness of the euro against the US currency.

FX swap market continues to grow

The 2019 BIS triennial survey notes that FX swaps are the most heavily traded instrument and continue to gain market share, accounting for 49% of total FX market turnover in April 2019, compared to 47% in April 2016. Cost is an obvious factor behind this growth, with ultra-low borrowing rates making swaps more cost effective than FX forwards, where the parties exchange a pair of currencies at a set rate on a future date.

Alfonso warns that the rise of FX swaps could be seen as a warning sign, given that financial institutions and investors use them to hedge risk. “Geopolitical uncertainty with Brexit, political drama in Italy and US trade wars on multiple fronts have given investors plenty to worry about, and FX swaps are seen as a simple way to hedge exposure to FX moves,” he says. “Swaps should continue to be an important part of overall FX turnover with volatility expected to remain lively as the US gets into election mode and Brexit continues to impact the pound.”

“The US economy is currently on more solid footing than the European economy, but headwinds such as the US-China trade war and political uncertainty have forced the Federal Reserve to cut rates once already with more to come in 2019, reducing the appeal of the US dollar,” says Alfonso Esparza, a senior analyst specialising in macro FX strategies for North American and major currency pairs at currency data and analytics firm Oanda.

Movements in the US dollar are followed particularly keenly because of its dominant currency status. The BIS survey reveals that the US dollar is on one side of 88% of all trades.

“The US dollar is a defensive currency and typically tends to strengthen when the global economy slows down or risk sentiment deteriorates,” says Meera Chandan. “To illustrate this point, 2017 was a period with strong global growth that was broad-based across countries and a weaker dollar. By contrast, global growth momentum slowed in early 2018, which ended up being USD-supportive.”

Fundamentals guide the direction of the US dollar, says Alfonso. A good example of this was when US president Donald Trump announced his intention to impose a 10% tariff on aluminium imports on 1 March 2018. “The US had already slapped tariffs on China, yet when it threatened to raise aluminium tariffs against a host of nations the US dollar was sold off across the board,” says Alfonso. “When the US announced exemptions on tariffs and once again concentrated on China the US dollar rose, as in that scenario it was still seen as the more likely safe haven and the currency to hold in the case of global trade uncertainty.”

Adam refers to a complex relationship between global growth and the US dollar. “The best way to understand it is the 'dollar smile', a theory popularised by former Morgan Stanley currency strategist Stephen Jen,” he says. This theory posits that the US dollar tends to do best when the situation is good or bad and sags in a middling economy.

For any medium-to-large economy, having its own currency is a net positive because it generally acts as a counterweight to whatever is happening in the economy

The strength of the US dollar is not only closely monitored by traders – it is also vitally important to emerging market economies. When these economies seek external funding, it is often denominated in US dollars as the lender will not want to have currency exposure on top of the country risk. This means more pain when the US dollar rises as it will increase the amounts needed to satisfy the loan, creating a particularly challenging environment for countries that struggle to generate significant US dollar revenues from exports.

Closer to home, the fallout from the EU referendum has served as a reminder of how even major economies can see their currency move sharply downwards against the US dollar. However, Tod Van Name, Bloomberg’s global head of FX electronic trading, points out that having its own currency enables a country to use monetary policy to mitigate financial or economic shocks.

For any medium-to-large economy, having its own currency is a net positive because it generally acts as a counterweight to whatever is happening in the economy. So, when trouble hits, the fall in the currency cushions economic weakness by making exports more competitive and by attracting foreign investment.

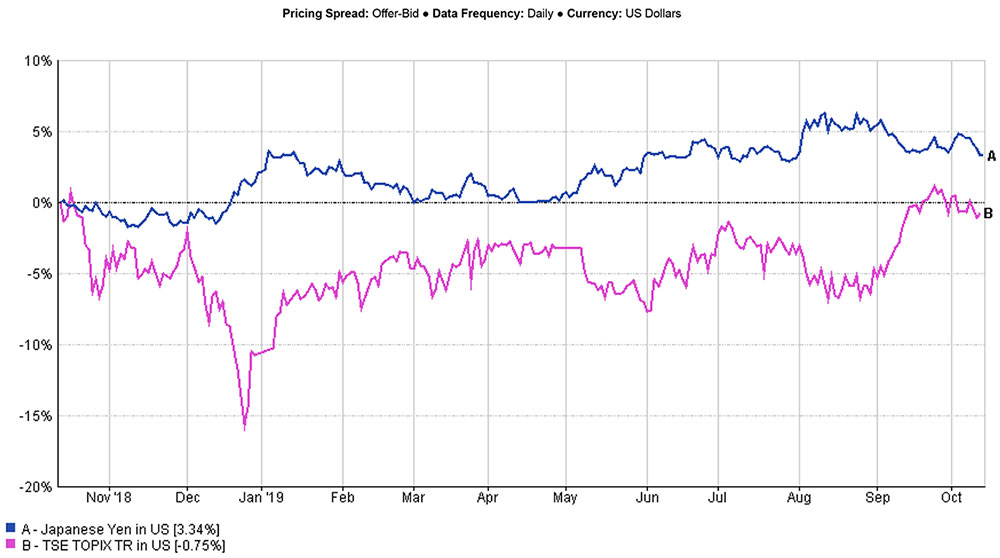

Tokyo Stock Price Index versus the yenThe chart below is an example of inverse correlation between the Japanese market and the yen, because Japan is largely an export led market.

Source: FE Analytics

Source: FE Analytics

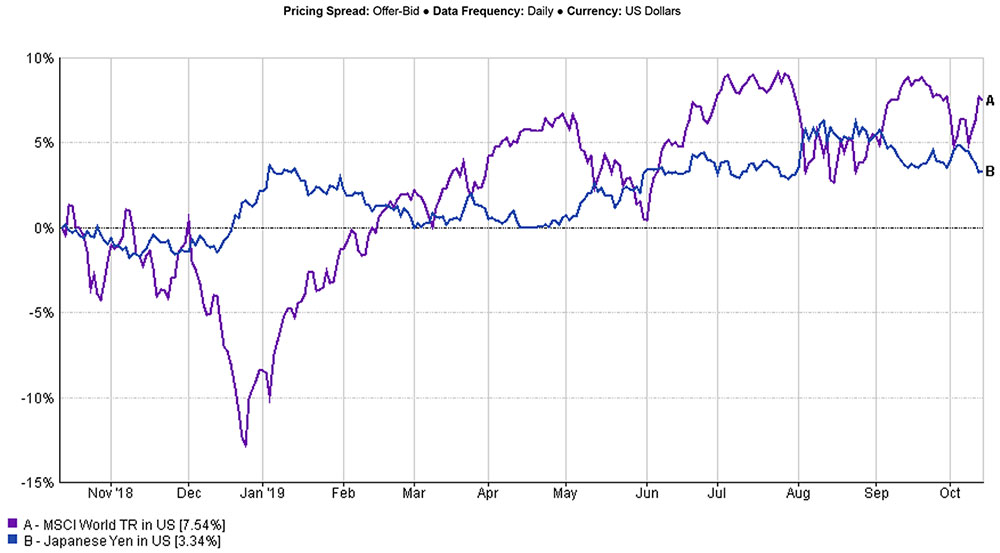

MSCI Index versus the yen The chart below shows the yen versus the MSCI World equity index, which are also inversely correlated because the yen is seen as a safe haven. Source: FE Analytics

Source: FE Analytics

“In smaller economies with open investment it can become a problem when there is capital flight,” says Adam. “For a country like the UK, having its own currency is undoubtedly a positive since the post-Brexit currency fall has stimulated exports and prevented what could have been deflation.”

Alfonso adds that since Brexit is a political event, the Bank of England will not interfere until it feels it needs to.

“The pound has depreciated as the process of leaving the EU while keeping commercial trade and borders intact has proven to be more difficult than expected,” he says. “A depreciating currency lowers the ability of citizens to buy imported goods but gives an edge to UK exporters as it raises their competitiveness in overseas markets.”

At various points in history the UK currency has been pegged to gold. While the Bank of England finally abandoned this link in 1931, recent geopolitical uncertainty has boosted the precious metal’s status as a safe haven. “Alternative asset classes have risen in value as geopolitical uncertainty has spilled over into worries about a possible recession,” says Alfonso. “Trade wars that could evolve into currency wars are boosting the demand for gold.”

The argument against gold has always been that it yields nothing and that bonds could provide the same level of safety while offering interest. In the world of negative rates that relationship has flipped. “Gold will continue to gain so long as we remain in a global central bank easing cycle,” says Adam. “The previous global central bank easing cycle ended with gold at US$2,000 and I expect that figure to be exceeded during this cycle. Add in political instability, quantitative easing and growing deficits and the outlook for gold is as positive as it has been in generations.”

Seen a blog, news story or discussion online that you think might interest CISI members? Email bethan.rees@wardour.co.uk.