Ever since the UK government deregulated financial markets in October 1986 – known as Big Bang – private share ownership has been commonplace among UK businesses. However, the legislation of the time encouraged mass share ownership – typically by institutions on behalf of investors – rather than by individuals in the companies for which they worked.

As a result, according to the Employee Ownership Association (EOA), there are just 370 employee-owned firms out of the more than 4.2 million registered businesses in the UK. But this number could be set to grow in response to predictions of a “huge drop” in access to advice in the coming years, according to the Heath Report Three, published in January 2019. It examines the availability and future of professional financial advice in the UK, covering 249 adviser firms representing 865 advisers. It says that unless advisers are replaced, the number of consumers accessing advice could be under one million within a decade, and it outlines key actions to take, including training and retaining advisers – see box below.

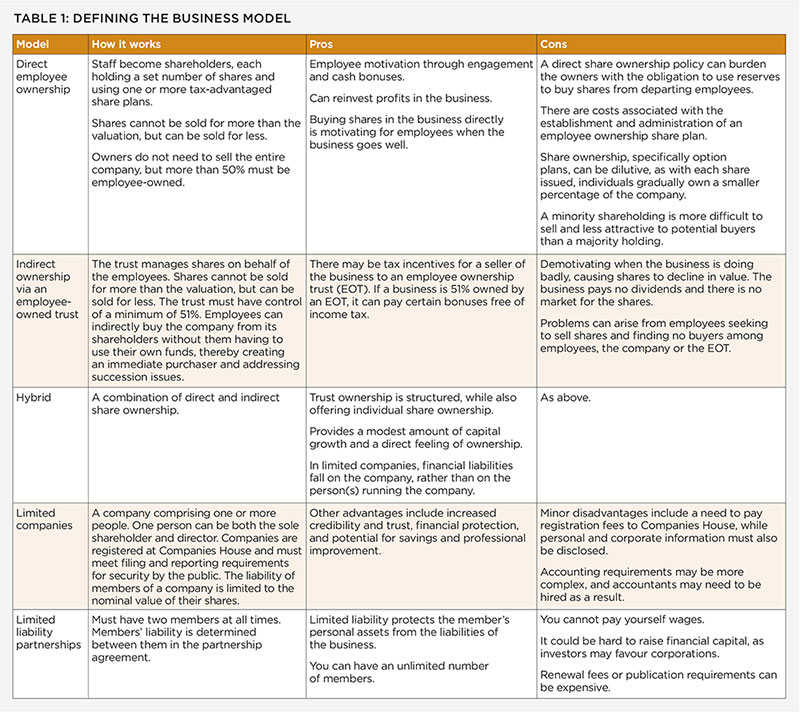

The EOA defines employer ownership as relating to British firms where “25% or more of the ownership of the company is broadly held by all or most employees (or on their behalf by a trust)”. Under direct employee ownership – or substantial share ownership – employees become registered individual shareholders of a majority of the shares in their company using one or more tax-advantaged share plans. Reasons to consider a direct ownership arrangement include a need by the retiring owners to retain some shares because the employees cannot afford to purchase their whole shareholding in one go, or capital may be needed to bridge a purchase price gap. In such cases, employees are invited to buy shares through a tax-efficient employee share incentive plan to make up the difference.

Under an indirect employee ownership model, shares are held collectively on behalf of employees, normally through an employee trust. Combined direct and indirect ownership means a combination of both.

What is the Heath Report Three?

The Heath Report Three, published in January 2019 by Libertatem, examines the availability and future of professional financial advice in the UK. It covers 49 adviser firms representing 865 advisers. The research aims to answer seven prime questions:

1. What is the current capacity of the professional financial advice sector?

2. Can the current adviser numbers be maintained?

3. What has changed since Heath Report Two (published in 2015)?

4. What are the trends in business models and how does that impact on the availability of advice?

5. Could advisers work in a smarter fashion to improve the number of clients they each handle?

6. What are the future capital needs of the sector?

7. What are the current challenges facing the financial services community?

The report finds that “Unless major changes are made across the board, only two million consumers will [be able to] access advice by 2030 – a huge drop from the historical capacity of 16 million.” The report calls on all stakeholders including advisers, HM Treasury, the FCA and the FOS to take the following key actions:

1. Change public policy to actively encourage consumers to invest and protect themselves and their families.

2. Add “encouraging consumers to invest and protect themselves” to the FCA’s current objectives.

3. Expand the number of consumers being advised.

4. Make a major investment in adviser training with an immediate target of training and retaining 1,650 advisers every year, eventually rising to 5,000 advisers.

5. Initiate a major review of barriers to entry, including capital adequacy, the actions of the FOS, professional indemnity insurance and regulatory costs.

Of those 370 firms that the EOA identifies, 60% converted from private to employee ownership following the 2014 Finance Act, which introduced a complete exemption from capital gains tax on the sale of shares to an employee ownership trust (EOT) – see table below for definition.

The 2012 government-commissioned Nuttall review of employee ownership also had an influence. Among the 28 recommendations, the review advises that government should encourage take up of EOTs and raise awareness of the benefits, reduce the complexity of the structure, and avoid regulatory burdens. Its author, Graeme Nuttall OBE, a partner in Fieldfisher’s Employee and Mutual Ownership Team, says the number of EOT businesses can only increase and believes financial planners are well suited to the model.

“Since the [2012] review, there are hundreds more employee-owned companies. Many architects adopted the employee-owned model, and now there is real momentum. I foresee something similar within the world of financial planners,” Graeme says. He explains that architect practices follow similar structures to financial planning firms, therefore he believes the model will work well for this sector, too.

Moving to an employee ownership structure is not just about benefits for the companies and owners. Employees also stand to gain substantially from taking a share in the business. First, there is the opportunity to benefit financially. Profits made will be returned to employees, and there is also the opportunity to gain tax breaks on bonuses and make contributions to retirement savings at no extra cost to the employee (see table). Employees are also more directly involved in the company’s objectives, since shareholders naturally have more of a say in how the business is run.

Whether the existing structure of a financial planning or advisory firm is a limited liability partnership (LLP) or a limited liability company, it is possible to convert to an employee-owned arrangement.

There is no size limitation. For example, consulting firm BDO says it worked with numerous companies from all sectors in 2019, including LLPs and groups, to establish EOTs. They have ranged from companies with just 20 employees to over 1,800, with values from £1m to over £80m.

Options to exit

Financial planners wishing to exit the business can enter a trade sale, a management buyout (MBO) or sell shares to employees directly or indirectly.

Chris Budd, who moved his own financial planning firm, Ovation Finance, to an indirect EOT structure in 2018, says the reasons for moving to an employee-owned arrangement are twofold: money and legacy. “I wanted my business to continue after I had left, and I wanted to receive a fair value. An EOT offers both those things,” he says. Neither a trade sale nor an MBO appealed to him, because with the former there was a danger that the “business could disappear along with your employees and clients”, and the latter because “it needs requisitely skilled employees with money”.

Getting buy in

Moving to a direct or indirect employee-owned arrangement is a relatively simple process, but it cannot be rushed. “It is easy to set up and it is an approved HMRC model, so it should be straightforward, but success depends on employee engagement,” says Chris, adding that it is a cultural shift and future profitability depends on employees buying into the new conventions. “You get paid from the future profit of the business, so you need to take time to prepare the business and the employees so that it will continue without you and therefore pay you.”

This success also depends on securing client support; they must be reassured that their service levels and access to expertise will not be jeopardised by the new structure. “The owner needs to make themselves the least important person in the business so that they can leave but the clients will stay,” Chris explains. “This is key to the process and may take a few years.”

Retention tool

If firms can achieve it, however, moving to either a direct or indirect EOT model is very powerful as an employee incentive, since their own motivations are aligned with those of the business. Critically, it is not just the typical fee-earning employees that are rewarded, which is a key difference from traditional performance-related bonus structures. Chris says all employees have a voice in an employee-owned business, with those who cannot earn fees still receiving a bonus, which helps them to stay motivated, remain with the firm and ensure its success.

Case study: Paradigm Norton

Paradigm Norton’s move to an employee ownership trust (EOT) was five years in the making and finally came to fruition in 2019. Barry Horner CFP™ Chartered MCSI, Paradigm’s founder and CEO, says it was critical to the management team that if anyone left, their legacy would be intact and that employees could shape their own future and that of the business for themselves. At the same time, clients had to receive equivalent service and support. Fortunately, the 2014 Finance Act had given new legitimacy to an age-old solution – the EOT – which was, Barry says, perfect for Paradigm.

“Employees could direct the future of the business, but the clients would not notice any difference,” he explains. Employees have already received their first bonus and the EOT is working well. “The team doesn’t need to think about what is around the corner, they can invest for the future and see they have a career here until they retire,” says Barry.

It is also reassuring for clients. “We have created a structure to allow team members to just continue with clients, and there is no fear that we will be taken over in the future.

”Barry says setting up the EOT was straightforward, but concedes that the firm benefited from having its own in-house tax and accounting specialists. However, Paradigm hired an external lawyer to ensure all the contracts were in place.

“The EOT won’t be for everyone,” Barry admits, “but it has ticked all our boxes.”

And unlike share incentive plans, which often require employees to sacrifice salary to own the shares, employees do not have to come up with money to receive profit from the EOT. Selling shares to just those employees who can afford it can be divisive, whereas employee ownership arrangements are designed to motivate everyone equitably.

Not for everyone

Moving to an employee-owned arrangement will not be suited to every business. Barry Horner CFP™ Chartered MCSI, founder and CEO of financial planning firm Paradigm Norton, which moved to an EOT structure in 2019, says, “We have a collegiate style of operating, so the EOT works well, but if you have a dictatorial management style, moving to an employee-owned model would be challenging.”

Graeme Nuttall agrees that employee ownership is not suitable for every business and highlights several other challenges with the model. “Once the majority of the shares are locked up indefinitely, it makes it less attractive to sell the company to a trade buyer and makes it harder to attract private equity investment, as there is no exit for the company.”

He adds: “Owners must be willing to share their profits with the many rather than the few, and they will mostly need to rely on loan finance because they won’t want to issue shares to third parties.” Ultimately, there is no hard and fast rule as to which companies are more suited to employee ownership, but companies need to have strong management teams delivering robust financial results to stand a chance of success.

Despite Chris’s view that employee-ownership structures are straightforward to set up, there can be challenges in finding legal support with the requisite skills, which may deter businesses from continuing. The Employee Ownership Association’s Employee ownership impact report says that “most professional advisers, drawn from legal, tax and accounting professions … lack a developed understanding of employee ownership” and because of this, “they often perceive that the legal complexities and financial barriers outweigh the benefits, and advise clients accordingly”.

Employee ownership has received a boost since 2014 and offers another option for financial planners wishing to exit the sector. But there is more to the EOT model than that; companies with an eye on securing the long term for themselves, their clients and their employees could do worse than give the workforce a true slice of the success.

This article was originally published in the February 2020 print edition of The Review.

The full print edition PDF is now available online for all members.

All CISI members, excluding student members, are eligible to receive a hard copy of the quarterly print edition of the magazine. Members can opt in to receive the print edition by logging in to MyCISI, clicking on My account, then clicking the Communications tab and selecting ‘Yes’.

Once you have read the print edition, keep coming back to the digital edition of The Review, which is updated regularly with news, features and comment about the Institute and the financial services sector.

Seen a blog, news story or discussion online that you think might interest CISI members? Email bethan.rees@wardour.co.uk.