All eyes are on banking, superannuation and financial services in Australia, thanks to the Royal Commission (set up in December 2017) looking into misconduct in the financial services sector.

Paul Resnik, co-founder of Australia-based risk tolerance house FinaMetrica, part of PanPlus Global, says he has been in the financial services sector for almost fifty years, but has “never witnessed something quite like this”. He describes the Royal Commission as “revealing the cancer of disrespect for clients. The cancer is that institutions just either don’t care, or don't care enough. It is fundamentally the lack of respect for clients, which results in a failure to provide to their advisers a framework for suitable advice".

The evidence the commission has revealed so far has shocked the public in Australia and across the globe, exposing egregious behaviour in the big five firms in Australia’s banking sector – Commonwealth Bank of Australia (CBA), National Australia Bank (NAB), Australia and New Zealand (ANZ) Banking Group, Westpac, and AMP, Australia’s largest listed wealth manager. The practices and culture of these firms have been slammed by the commission.

Among the revelations so far are that:

- Thousands of NAB customers had their planners falsify documents relating to their finances in 2016. A senior executive admitted that the practice was a “social norm” within the bank. Also, the commission heard that bosses at NAB knew about widespread fraud months before telling the regulator, in 2015.

- AMP charged fees for no service, admitted that it lied to the regulator over 20 times from 2015 to 2017, and made customers “self-request” refunds for advice they hadn't received, from 2009 until 2017.

- ANZ forged signatures, used the power of attorney fraudulently and maintained remuneration structures for advisers that were not in consumers’ interests, in the 12 months to July 2016.

- CBA charged fees for financial advice to some deceased people, in one case for a decade. The commission heard examples of this dating back to 2004 until recently.

- Westpac will pay AUS$35m in fines after wrongly assessing people's ability to repay mortgages. This is in relation to about 100,000 home loans from 2011 to 2015.

There have been consequences to the revelations. In April 2018, AMP announced the resignations of its chairwoman and legal counsel. More than AUS$2.2bn, or roughly a fifth of its value, was wiped off its market capitalisation in two weeks.

The latest round of hearings, round six, began in Melbourne on 10 September 2018, focusing on insurance. Revelations include an admission by life insurer TAL that it bullied a customer over an eight-year period, hiring a private investigator to help it find a way to stop paying a client insurance benefits. Another insurance firm is also under fire – Clearview Wealth, the former life insurance arm of high-profile insurer NRMA. The commission heard that it had committed 300,000 criminal breaches when cold-calling customers.

On 11 September, Reuters reported that law firm Slater & Gordon will file class-action lawsuits against CBA and wealth manager AMP for giving customers “ludicrously low” or negative returns without justification.

And on Friday 28 September, the commission released its interim report. Banking association chief Anna Bligh reacted to the release to reporters in Sydney: “Today is a day of shame for Australia's banks. Having lost the trust of the Australian people, we must now do whatever it takes to earn that trust back.” In the executive summary of the report, Commissioner Kenneth Hayne blames greed for the misconduct in financial services, pointing the finger not only at financial institutions, but also regulators for not being robust enough in seeking "public denunciation of and punishment for misconduct".

Public concernThe creation of the Royal Commission was a response to a groundswell of public concern in Australia about the financial services sector, which is highly concentrated. Some events leading to the commission include allegations by the Australian Securities and Investments Commission (ASIC) against the life insurance arm of CBA for malpractice. This came shortly after ASIC sued ANZ Banking Group for alleged manipulation of Australia’s benchmark interbank borrowing rate and imposed additional licence conditions on Macquarie Group for mishandling client money.

The commission has a sweeping remit to look at allegations of misselling, fraud, bribery, deceiving regulators and unethical customer practices with a view to instigating legal proceedings if appropriate.

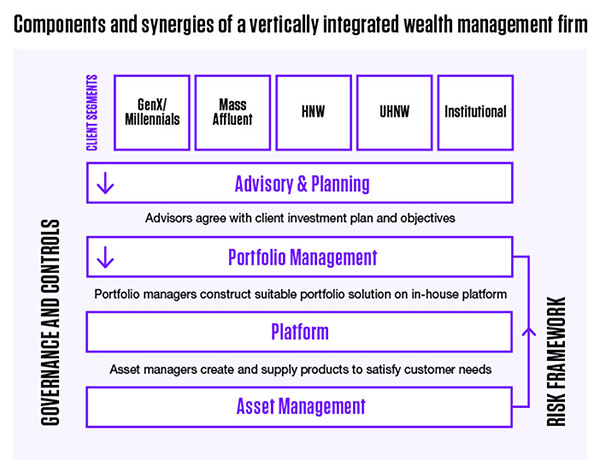

The model of vertical integration in wealth management – the combination in one firm of two or more stages of the planning process, normally operated by separate firms, such as in the mortgage sector, where firms might have divided responsibilities for brokering, originating, servicing, and securitising loans – has come in for particular blame.

The intention may be to benefit from scale, reduced costs, agility and greater opportunities for innovation in the face of difficulties to maintain profitability (see diagram below), but there are inherent risks in vertical integration. One is conflicts of interest, with vertically integrated wealth managers providing advice to their customers while acting as financial product manufacturers (to use the Markets in Financial Instruments Directive term), providers and distributors of internally-produced and third-party products.

Source: Capco's Vertical integration for wealth managers

ASIC published a 53-page report, titled

Financial advice: vertically integrated institutions and conflicts of interest, on the subject in January 2018, just before the Royal Commission began its hearings, showing the proportion of in-house products versus external products bought (see diagram below). Among its findings was that, although companies offer a good range of external products, after talking to the firms’ advisers, a huge proportion wind up opting for the in-house offering.

Source: ASIC's Financial advice: vertically integrated institutions and conflicts of interest

The Australian inquiry publishes its full report in February 2019, but the impact on the vertical integration model is uncertain. Australia-based consumer advocacy group Choice has submitted some recommendations to the Royal Commission, including: “The commission further explore the impact of a separation between advice and products sales as one of a suite of measures to address poor quality financial advice.” An opinion piece in the

Australian Financial Review warns the regulators against a ‘knee-jerk’ move to over regulation, while an article in

The Sydney Morning Herald states flatly that “the big banks’ vertically integrated wealth management business is finished”. And Australia-based

Money Management reports that “it seems likely that one outcome of the Royal Commission is that the vertically integrated business model will be substantially diminished or even banned”.

On the retreatIndeed, many of the big banks do seem to be retreating from wealth management, in part, although this may be due to the falling profitability as much as the reputational damage.

It had been an open secret for some time that NAB, for example, was contemplating an exit from its wealth management business – something its head, Andrew Thorburn, confirmed in May by announcing a demerger and float or trade sale of its MLC business. This follows ANZ's exit from most of its wealth advisory and insurance businesses and the CBA undertaking a study to float its Colonial First State Asset Management arm.

Critics of vertical integration see it as always flawed, while supporters see it as merely needing careful handling, with strict governance rules in place.

According to the

transcript for NAB’s 2018 Half Year Results media conference, Thorburn says: “The problem for the banks generally isn’t so much the vertical integration of their wealth management units, nor particularly the co-existence of banking and wealth management. The rotten core of the issues aired at the Royal Commission is the character, conduct, competency and conflicted behaviours of some advisers and the financial incentives that drive/corrupt some of the advice.”

Paul from FinaMetrica argues that Thorburn, as the man at the top, needs to take ultimate responsibility for the culture within his company and the advice it gives. He warns that if vertical integration is merely left to regulation and enforcement, it will fail. For him, coping with vertical integration’s inherent problems has a moral and cultural dimension: it will only work where staff are imbued with moral values, where incentives don’t foster ethical shortcuts and where organisations at the very top support staff to resist pressures for a quick profit. Transparency about conflicts of interest due to flawed disclosures on fees, ownership and inappropriate explanation of investment risks are, in his view, imperative. The investor’s properly-informed consent is an imperative to suitable advice.

Lessons for the UKSo, what lessons should be learnt by the UK from the Australian scandals? In an interview for

The Review, Ned Cazalet, former adviser to the Treasury and the Financial Services Authority, says Britain had a torrid time of it in the 80s and 90s when there was “a wild west mentality”. Misselling was rife and hiding fees from the clients paying for them was elevated into an art form. Things have, he believes, improved markedly.

True, several leading UK wealth management companies do rely on vertical integration. But the structure of the UK financial services sector differs significantly from that of Australia’s. Most notable is that the big banks in the UK are not the biggest players in providing wealth management products. There is a strong expectation that the Royal Commission will move to professionalise the sector, much like what the FCA did with its Retail Distribution Review in 2013, which impacts on the way financial services are delivered to retail investors in the UK – but this is expected to be more extensive.

The FCA has agreed the need to clarify the rules around vertical integration, which will include the issue of conflicts of interest. And the UK institutions’ activities will continue to be subject to various public criticism. But for the moment, the hue and cry against the financial institutions in Australia over vertical integration is unlikely to be replicated directly in the UK.

The wider global impact is yet to be felt – in part because the dominant banks in Australia are local. But the findings of the Royal Commission, once published, will be scrutinised by regulators globally to see what they reveal (not least about the culture of the sector), and whether the authorities plan to impose a new phase of regulatory tightening.

Seen a blog, news story or discussion online that you think might interest CISI members? Email bethan.rees@wardour.co.uk.