It is the enduring cliché: what gets measured gets managed.

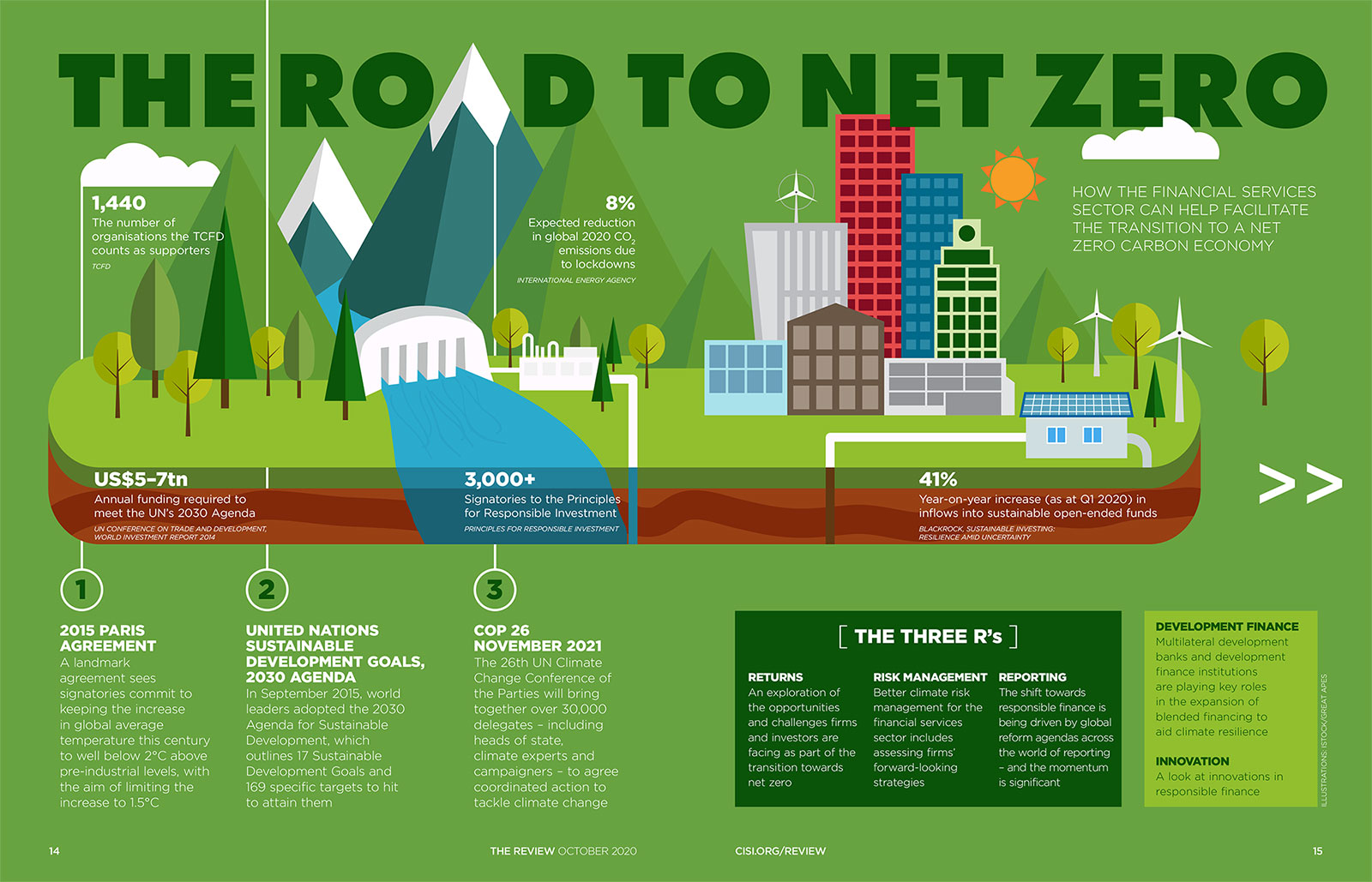

The Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD) has become, as Mark Carney said in February, the go-to standard for consistent, comparable and efficient information. "Most importantly", he said, "it represents the best views of the private sector of what is decision-useful, capturing the opinions of both the companies that must access finance and of the providers of capital from across the financial system." This is an important foundation towards ensuring that every financial decision takes climate change into account – the means of putting the information into the management process that will transform climate risk management and move everyone closer to a point where investing for a net zero world will go mainstream.

All this will mean work on both sides of the equation, with investors worldwide demanding both disclosures from corporate preparers of annual reports and also from borrowers and portfolio companies. This would steadily build the availability and quality of data that investors need to integrate responsible finance into their investment processes. In many ways these disclosures and their effect are the tip of the iceberg. They force businesses to think in the language of risk. It is all part of a wider movement and one that is gaining momentum. It should come as no surprise that Larry Fink, CEO of BlackRock, the world’s largest asset manager, made exactly the same point in his 2020 annual letter to CEOs.

The letter made it clear that sustainability will be at the centre of the firm’s investment approach. By the end of 2020, BlackRock expects clients to report in line with both the TCFD and the US-based Sustainability Accounting Standards Board (SASB). The changes afoot in the reporting world are all part of this wider movement. Many other areas of the technical and political forces moving in this same direction are increasing their momentum.

.jpg?sfvrsn=5b187109_0)

Paul Druckman has been bringing about change in reporting since the turn of the century. He headed up the Prince’s Accounting for Sustainability (A4S) project, set up in 2004, and served as CEO of the International Integrated Reporting Council (IIRC) between 2011 and 2016. "Reporting influences behaviour because it is the way companies and management are held to account," he says. In Paul’s opinion, it influences everyone from the C-suite to the board and management to the shareholders and the wider world of stakeholders.

These days he is chair of the World Benchmarking Alliance overseeing the creation of the means to measure and compare corporate performance on the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals. It is another way of providing the information that will influence and encourage change. By creating simple benchmarks and rankings for the companies that are the most influential on the planet, it hopes to build a dialogue that will create change. It will provoke the discussions that will alter behaviour in the reporting world. "Why is my pension provider investing in a particular company when it is ranked so low?" is the sort of question Paul wants to draw into the debate. These are examples of the sort of momentum that is building.

"Do I have the right information about the company I am investing in and do I believe it?"

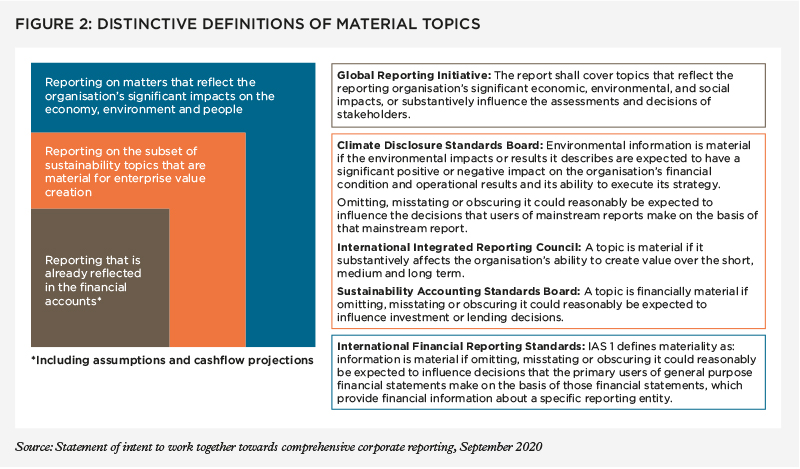

We are also in the midst of a pandemic that is underlining as never before the need for resilience and sustainability. There is a need to bring certainty to the connection between information and management decisions. In the words of Robert Eccles, visiting professor of management practice at Saïd Business School at the University of Oxford and the original founding chairman of SASB, "companies want standards for the non-financial information they are already reporting and investors want them for the non-financial information they are already using." Or as Veronica Poole, Deloitte’s global head of corporate reporting, puts it: "Do I have the right information about the company I am investing in and do I believe it?" She argues that mainstream financial reporting has a structure that is embedded in law and corporate governance codes; the legislative issues are supported by enforcement, and directors have to give personal assurances. It creates the right infrastructure for financial information.

But when it comes to sustainability or other non-financial information, none of these elements really exist. There is not a common understanding of what data people want, or what they need. Levels of assurance or internal controls all differ. And often much of the information is either never seen by, or never reaches, the boardroom. "There is very little board ownership, or controls," Veronica says. "So the data is disconnected. It is a fundamental issue. There are a plethora of standards and little rigour." The idea of change has an inevitability about it. There are signs that out of the combination of momentum towards workable solutions, and the recognition of an overriding need for resilience that the effects of the pandemic have created, the world will change.

Robert Eccles, who has been round the block on all this for years, simply says that "now is the time for the children to quit fighting"

In December 2019, Accountancy Europe, a pan-European grouping of accounting bodies, published a paper titled Interconnected standard setting for corporate reporting. Shortly afterwards, the European Commission announced that it intended to set European non-financial reporting standards and also review its non-financial reporting directive. There was a definite feel of tectonic plates accelerating in their movements. The global financial reporting standard setter, the IFRS Foundation, also let it be known that "financial information and non-financial information should be connected in order to enable decision-useful information" at the inaugural meeting of the Green and Sustainable Finance Cross-Agency Steering Group in May 2020. The other side of all the interested parties making their desire for change and harmony clear is the often labyrinthine and enormously convoluted way in which they could all be brought together. Robert Eccles, who has been round the block on all this for years, simply says that "now is the time for the children to quit fighting".

The crisis created by the pandemic is also playing its part. It may be that all the participants globally recognise that this combination of the pandemic and momentum has created a point where urgent and historic decisions need to be taken. The business and investment worlds need to join in forcing it forward. The building blocks are all there. The urgency with which it is required needs to be harnessed. The pandemic has focused minds and has made the central themes more solid: the interconnected nature of the issues, nature itself, risk, the need to deal with all the underlying inequalities and the social dimension. More emphasis will need to be placed on an organisation’s impacts on stakeholders and society as a whole. It is about mutual benefit, trust and shared values, the value creation for an organisation being linked to the value created for others. All these have come to the fore much more clearly and there is an understanding that they can’t be isolated anymore.

"In my view 2019 was the most inspiring year and we came into 2020 with real hopes of change"

"A lot has happened in the past six months," says Veronica Poole, "and that has been driven by how fast our society is changing. The pandemic has been a loud warning bell. The soundness of strategy and governance and the resilience of companies are all affected by these issues. There is a blunt realisation that this goes to the core of the survival of humanity." The likelihood, as the months ahead unfold, is that the building blocks will shift and a global framework will emerge. The reluctance to make disclosure, assurance, and enforcement mandatory will probably evaporate.

For years, the idea has been that voluntary frameworks that evolved were the best way to progress, as it avoided the fate of it becoming an imposed system that, as a perceived tick-box exercise, would not gain the credibility that an ultimately voluntarily accepted system would have. But the view, as the pandemic has added its urgency, has changed. Many now see that a mandatory system must be created and that there is not much time to waste in getting to that stage. "It has to happen soon, or it will be lost," says Robert Eccles. The knowledge and understanding is there, as is the will to put it all into place.

"It is going to happen," says Paul Druckman. "In my view 2019 was the most inspiring year and we came into 2020 with real hopes of change. The pandemic has held it back, but the senior players in all these fields have had time to talk to each other. I am much clearer about how it can be solved." The combination of global emergency and a belief that the world of reporting can finally implement its solutions could well be overwhelming in the coming years.

Click to enlarge

The full article was originally published in the October 2020 flipbook edition of The Review.

The full flipbook edition is now available online for all members.

All CISI members, excluding student members, are eligible to receive a hard copy of the quarterly print edition of the magazine. Members can opt in to receive the print edition by logging in to MyCISI, clicking on My account, then clicking the Communications tab and selecting 'Yes'.

Once you have read the print edition, keep coming back to the digital edition of The Review, which is updated regularly with news, features and comment about the Institute and the financial services sector.