The FCA defines credit card customers as being in persistent debt if they have paid more in interest and charges than they have repaid of their borrowing over an 18-month period. In July 2019, persistent debt was affecting more than three million people in the UK, according to the FCA. In the US, a recent survey by CreditCards.com finds that 23% of US adults with credit card debt have added to it during the pandemic.

To illustrate the cause of persistent debt, the FCA gives the example of a customer who borrows £3,000 on a credit card with an annual percentage rate (APR) of 19%. If they only make the minimum repayments, they will typically take 27 years and seven months to pay it off and pay £4,192 in interest.

Changing usage

Adam Butler, policy manager at StepChange Debt Charity, sees the roots of persistent debt in a long, gradual shift in the way credit cards have been used. “The original use of credit cards was based around the monthly repayment of the entire balance,” he explains. “However, it has increasingly been normalised to use a credit card to borrow for longer periods.”

Another issue is evolving working patterns. In a 2017 report, Reaching the poor: the intractable nature of financial exclusion in the UK, the Centre for the Study of Financial Innovation (CSFI) says: “In the absence of savings, many poorer people need credit to deal with the lumpiness of income and expenditure. This has been exacerbated by changes in work patterns that have seen fewer people in permanent employment with a regular salary, increasing numbers of self-employed people – including some on zero-hour contracts – and people moving in and out of part-time employment and benefits.”

Meanwhile, there was a sustained squeeze on real wages in the wake of the financial crisis of 2008, with wage growth falling sharply and remaining subdued until 2015. A spike in wages and record low inflation then brought some relief to household budgets, but consumers’ incomes were still being stretched even before the Covid-19 pandemic initiated a new crisis. According to the Money Advice Trust’s 2018 report A decade in debt, UK households owed £675bn in debt in 2000, representing 93% of their disposable income. In 2017 this had risen to £1,732bn and 133% of disposable income.

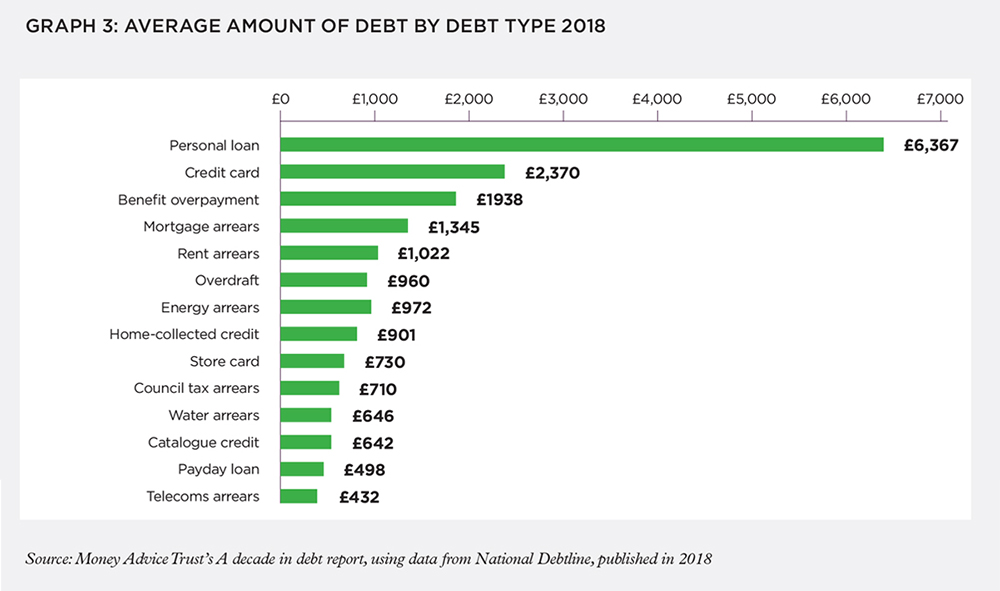

Data from National Debtline cited in the report shows that credit cards are the second biggest contributor to this debt, behind personal loans:

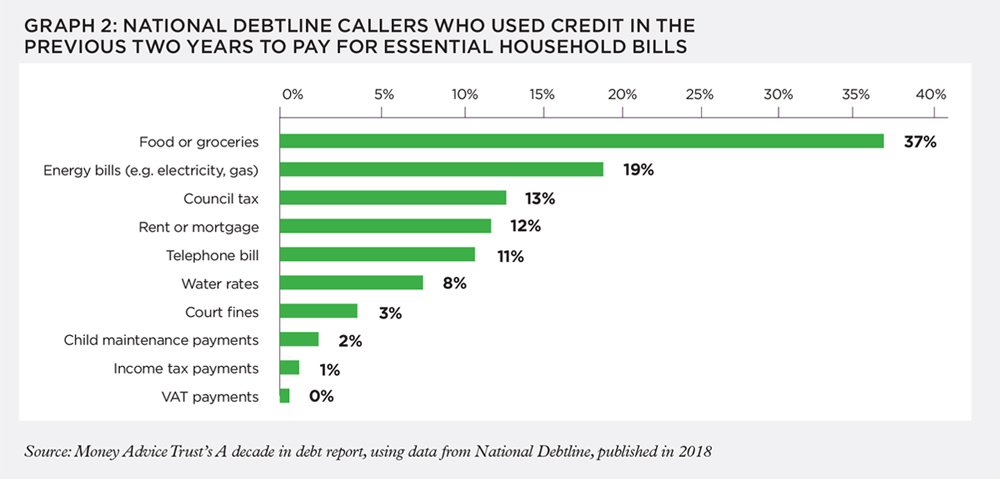

Adam says: “What makes credit card debt particularly problematic is that when people are experiencing other financial pressures, they often turn to credit cards as a way to meet day-to-day living expenses, which may be a short-term solution but can store up and exacerbate a longer-term debt problem.”

This is borne out by data from National Debtline:

A further problem is highlighted by a report StepChange published in 2019 that examines the link between sub-prime credit cards and problem debt. It finds that around a third (32%) of people with serious problem debt have a sub-prime credit card (high interest, often around 30–70% APR). Launching the report, StepChange CEO Phil Andrew said: “Our research points to a vicious circle. If you’re in debt you’re quite likely to take out a sub-prime card; if you have a sub-prime card it’s quite likely to exacerbate your debt.”

Andrew Hilton, director of the CSFI, and one of the authors of the Reaching the poor report, believes that one reason levels of credit card debt are so high is that other forms of lending (such as payday loans) are even more expensive and consumers have few alternatives. The CSFI report identifies credit unions as one such alternative, but finds that they are not widespread:

Credit unions have existed in Britain since the mid-nineteenth century. But, unlike in many other countries (e.g. Ireland, where more than 70% of the population belongs to a credit union), they did not expand in the mainland UK into full-service, modern financial institutions. Instead, they largely remain small local cooperatives, offering limited savings and loan services. Few had a high street presence and, even now, they rarely offer electronic or mobile banking facilities.

National differences

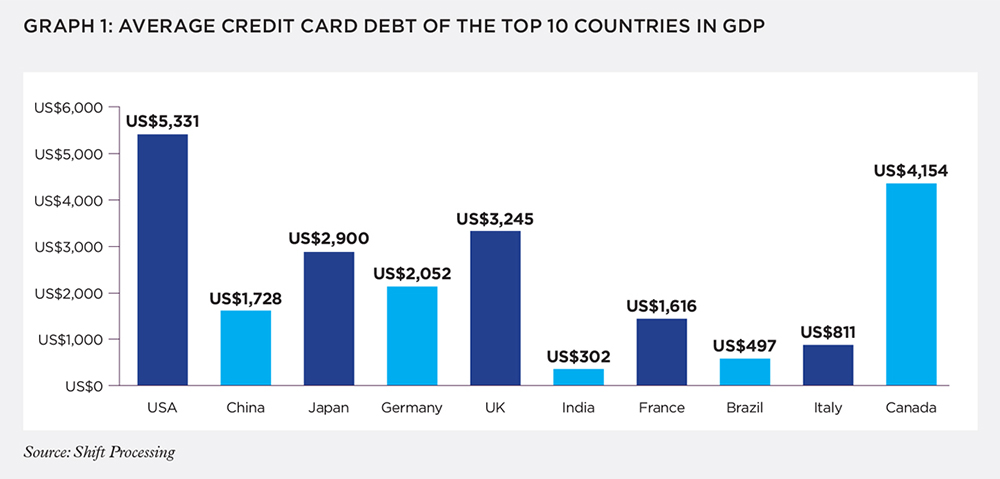

Among the world’s top ten countries by GDP, only the US and Canada have higher levels of average credit card debt than the UK:

The reasons for this disparity are complex and varied. Andrew Hilton points out that the UK has the most sophisticated economy in Europe and consumer credit is deeply entrenched: “By and large, other European countries are less ‘financialised’, though they are all heading in the same direction,” he says.

Specific national circumstances can be a factor; for example, in the US, which does not have free universal healthcare, many people use credit cards to pay expensive medical bills.

Culture also plays a part. Germans in particular have a long history of preferring cash to cards. Until recently, many major supermarkets and retail chains in Germany would not accept credit cards at all, and it was only in 2018 that the amount spent on cards overtook the total paid in cash. This has accelerated during the Covid-19 crisis, due to fears about passing on infection via banknotes. Mastercard International, for example, says it has seen “phenomenal growth” in the use of contactless cards across Europe – although this includes debit cards as well as credit cards.

Another cultural issue is the attitude of society at large to debt. Andrew comments that there is “a relative absence of social sanctions if you default on debt in the UK,” whereas in other countries, such as Germany, there is a social stigma attached to severe debt.

A third factor is legislative differences. For instance, usury laws are common in southern European states, placing a cap on the amount of interest lenders can charge on credit cards and thus helping to limit individual debts.

Under Italian usury law, the overall cost of the loan for the borrower cannot exceed a specific threshold. Spain’s usury law does not specify a rate above which a loan is defined as usurious, but borrowing costs should not be ‘significantly above' the normal cost of credit. A Supreme Court ruling in March 2020, that a 27% annual interest rate applied to a revolving credit card by online bank WiZink was considered usurious, could have wider implications for Spanish lenders.

Stopping the rot

The UK has led the way in attempting to address the problem of persistent debt. In November 2014, the FCA launched a study of the UK credit card market, analysing the account activity of 34 million customers over five years. The resulting report, published in July 2016, identifies two main causes of unaffordable borrowing: significant life events (such as divorce, redundancy and severe illness), and borrowing and repayment patterns.

It also finds that, while customers who default on their credit card repayments entirely are extremely unprofitable for card providers, “firms have fewer incentives to address consumers with persistent levels of debt or who repeatedly make minimum payments as these consumers are profitable, and we found that most firms do not routinely intervene to address this behaviour”.

After a period of consultation, in March 2018 the FCA launched a package of remedies aimed at helping those in persistent debt. The rules, which came into full effect in September 2018 (although some providers began implementing them earlier), set out a three-stage process:

1) 18 months: When a customer has paid more in interest, fees and charges than they have repaid of their borrowing over an 18-month period, the card provider will contact them to explain the benefits of increasing their repayments. They will also explain where to get debt help and advice.

2) 27 months: The firm sends the customer a reminder if the customer looks likely to remain in persistent debt at 36 months.

3) 36 months: The firm will offer the customer options to repay their balance more quickly. They will treat customers who cannot do this with forbearance, which could include reduced interest, fees and charges.

Adam welcomes these measures but calls for earlier intervention. “While there is in principle a requirement for firms to address affordability at the outset,” he says, “our report finds numerous examples of sub-prime card issuers increasing people’s credit limits at a time when it has become clear they are struggling. We would like to see a stronger focus on requiring firms to spot possible problems at an earlier stage so that fewer people slip into persistent debt in the first place.”

In other countries there has been less direct action to address credit card debt. For example, the Australian Securities & Investment Commission (ASIC) published a report in July 2018 titled Credit card lending in Australia, which identifies 930,000 people (approximately 4% of the population) as being in persistent debt (which ASIC defines as a situation where “the average balance of the credit card is 90% of the credit limit over the previous 12 months and interest has been charged”).

However, ASIC stops short of imposing conditions on lenders, concluding instead: “We expect credit providers to proactively look for signs of problematic credit card debt. The steps that should be taken vary based on the severity of the problems and how long they have persisted.”

Pandemic response

The providers that adopted the FCA’s recommendations in September 2018 began sending the appropriate letters to customers who had been in persistent debt for 36 months in March 2020. However, the impact of the Covid-19 pandemic has interrupted this timetable. In a statement on 17 March, the FCA says: “Given the challenges facing many customers at present we think they should be given more time, until 1 October 2020, to respond to firms’ communications. This means that firms would not be obliged by our rules to suspend the cards of non-responders before then.”

The FCA has also introduced new temporary measures to help people struggling with repayments. Lenders are now expected to offer consumers negatively impacted by Covid-19 a temporary payment freeze on loans and credit cards for up to three months, without any negative impact on their credit file.

However, there is no requirement for providers to stop charging interest on outstanding credit card balances during this payment freeze – so, while it may offer relief to struggling consumers in the short term, it may actually increase their problems in the long term. Adam comments: “The payment holidays and temporary forbearance put in place by creditors will eventually need unwinding, but the way in which this is done will be crucial if those in difficulty – potentially hundreds of thousands of people – are to avoid a debt spiral.”

The suspension of the three-step sequence of written notifications also means that it will be some time before the FCA is able to assess whether the programme as a whole is having the desired effect, though the statistics that are available to date suggest that it may be. Jackie Barodekar, director, cards and consumer credit at trade body UK Finance, writes in an article for the UK Finance website: “The FCA’s forecast for accounts in persistent debt at the first wave of 36 months was around two million. Due to the success of the earlier rounds of communication, industry data shows that this is likely to be a lot less – nearer to 1.1 million accounts, or around 950,000 customers.”

It’s also noteworthy that, according to statistics from the Bank of England in November 2019, there was a net repayment of credit cards for the first time since July 2013. And, according to UK Finance data, the annual growth rate of outstanding balances on credit cards stood at 3.0% in December 2019, continuing a downward trend from the recent peak of 8.3% at the start of 2018.

The long-term effects of the pandemic on the personal debt landscape are impossible to predict, with varying national customs and trends in credit card usage complicating the picture. When we come out of the other side of Covid-19, financial planners are likely to be dealing with debt management, as well as their wealth management responsibilities.