When we talk about a country having a negative interest rate policy, we refer to the interest rate paid by banks on deposits with their respective central banks. In countries that have a positive interest rate policy, the central bank pays interest to banks for the deposit they hold. In the UK, this is known as the bank rate, in the eurozone, the deposit facility rate, and in the US, the federal funds rate.

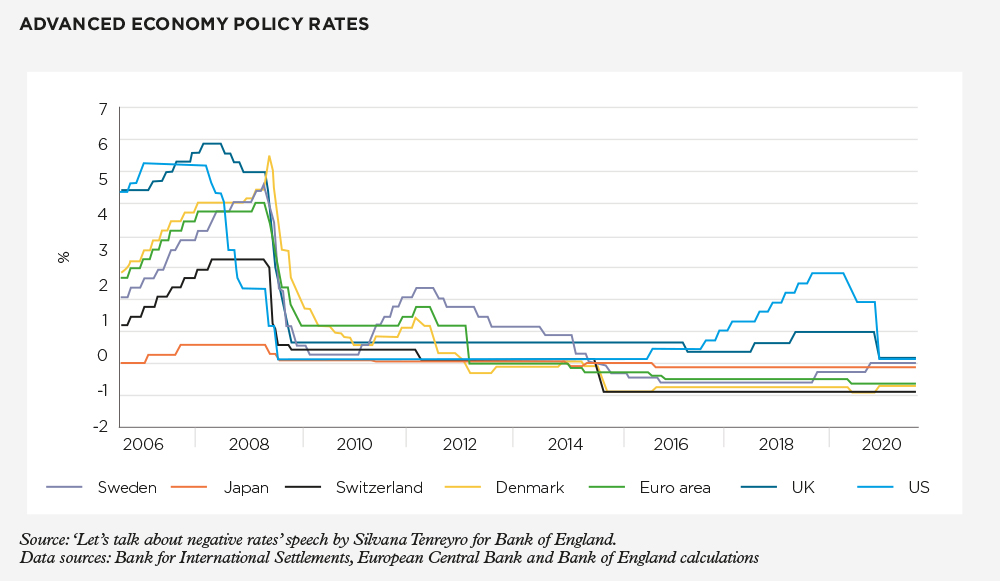

In the early-to-mid 2010s, in the wake of the global financial crisis and eurozone sovereign debt crisis, the adoption of negative interest rates became more common, as mentioned by Silvana Tenreyro, external member of the Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) at the Bank of England (BoE), in a speech titled ‘Let’s talk about negative rates’ in January 2021. Denmark ‘went negative’ in 2012, as did the eurozone and Switzerland in 2014, Sweden in 2015, and Japan in 2016. The main reasons central banks cited for their decisions were to stimulate inflation, which was running below target ranges in the cases of the eurozone, Sweden, and Japan, and in the cases of Denmark and Switzerland, with policies of controlling the exchange rate of the krone and franc respectively against the euro, to depress the value of their currencies. Only Sweden has subsequently moved out of negative territory, raising its ‘repo rate’ to 0% in 2019 as inflation had stabilised close to a 2% target.

The UK recently took a step closer to negative rates. In October 2020, the BoE started an operational readiness assessment of a negative bank rate, and in the speech, Tenreyro said: "Looser monetary policy can help the economy recover faster, bringing inflation back to target, while also preventing some of the job losses and business failures that could otherwise reduce potential output in future … It is possible that more stimulus [will] be needed to do so at an appropriate pace. If that is the case, having negative rates in our toolbox will, in my view, be important."

The US has not inched as close, but the policy certainly received serious consideration at the height of pandemic-induced economic uncertainty. Yi Wen, assistant vice president and economist at the Federal Reserve Bank of St Louis (one of 12 operating arms of the Federal Reserve System, or ‘the Fed’), wrote in a May 2020 article, 'How to achieve a V-shaped recovery amid the Covid-19 pandemic': "A combination of aggressive fiscal and monetary policies is necessary for the US to achieve a V-shaped recovery in the level of real GDP. Aggressive policy means that the US will need to consider negative interest rates and aggressive government spending."

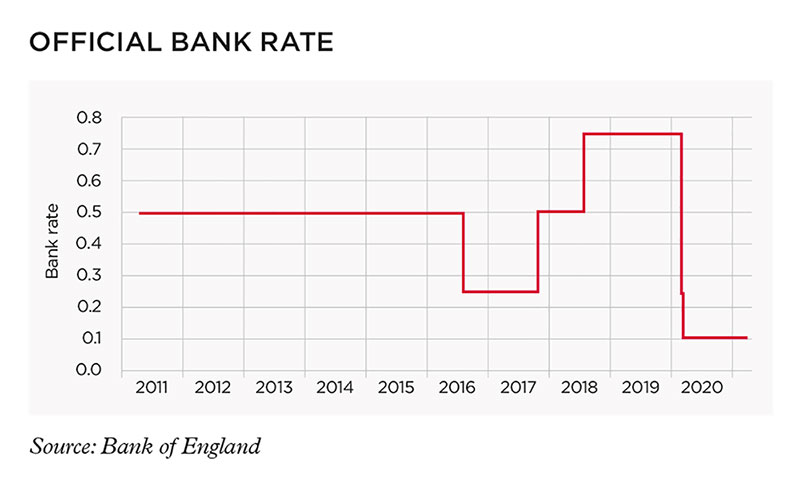

More recent statements by both UK and US central banks suggest the likelihood of negative rates has receded, but is not off the table. On 17 March 2021, The BoE MPC unanimously voted to maintain the bank rate at 0.1%, saying its existing stance remained appropriate. This was in light of a February 2021 upgrade to the UK’s economic outlook and subsequent "developments in global GDP growth" that had been "a little stronger than anticipated". It does however state that the outlook for the economy remains "unusually uncertain", that it will monitor the economic situation closely and that the MPC "stands ready to take whatever additional action is necessary".

"Banking is extremely competitive in Germany and these pressures have kept them from passing rates on"

Also on 17 March 2021, a similar situation unfolded in the US. The Federal Open Market Committee voted to keep its target rate at 0.1%. At a press conference, chair Jerome Powell said the "recovery has progressed more quickly than generally expected", but that "the economic recovery remains uneven and far from complete, and the path ahead remains uncertain". He also indicated that interest rates were expected to be maintained at between zero and 0.25% until employment and inflation targets were met, but that the Fed was committed to using its "full range of tools" to support the economy.

While it is looking less likely that the UK, US, or others will cross the line into negative rates, wealth managers, financial advisers and financial planners may want to consider its potential effect on their advice and on clients’ financial affairs.

Experiences from the ‘negative club’

A common feature from countries that have introduced negative rates is that they are typically not passed on to retail bank customers en masse, if at all. But this can change if negative rates prevail for an extended period.

In Sweden, according to the Riksbank, negative rates were only passed on to larger companies and parts of the public sector, not to households. It suggests that this was due to banks having perceived the negative policy rate as temporary.

In Germany, however, the situation has evolved substantially since 2014. For the first few years, it was rare for negative rates to be passed on to the consumer. According to Sebastian Schaefer, German FSO consulting wealth management leader at consultancy firm EY: "Banking is extremely competitive in Germany and these pressures have kept them from passing rates on. By mid-2019, only a handful of banks had done so and then mostly on larger balances, typically above €100,000 or even above €500,000."

Sebastian also points to a legal case between a consumer protection association and a bank being responsible for some banks delaying their decision. In January 2018, the Tubingen Regional Court ruled that imposing negative interest on a consumer's existing deposits by unilaterally changing the terms and conditions of the account was unlawful. One of the reasons was that it would constitute a material deviation from the fundamental relationship. A cash deposit is in effect a loan to a bank, and a bank imposing a negative interest rate would mean that a customer would be obliged to pay a fee instead of receiving remuneration.

"With yields so low in the closest alternatives to cash, such as gilts, fees are very important to consider"

But as 2019 progressed, the trend towards passing negative rates on to consumers accelerated. Sebastian says that low profit margins for banks, exacerbated by the economic fallout from the Covid-19 pandemic in 2020, led to many more passing negative rates on. By February 2021, comparison site Biallo.de reports that 322 banks (out of a study of 1,300) were charging negative interest rates to new customers, with around one third of these charging negative interest on balances of €25,000 or less.

Sebastian stresses that the impact on wealth management has been an evolution since interest rates started falling in the wake of the global financial crisis, rather than the result of the ‘event’ of moving into negative rate territory. He says the main consumer investing trends are a gradual shift into investment products that provide positive real returns over time, such as equities (he points to the rise of low-cost exchange-traded funds being an accelerant to this trend) and also investment into housing "as the price of mortgage loans dropped with lower interest rates".

How UK banks might react

Silvana Tenreyro, in her January 2021 speech, stressed that a negative bank rate in the UK does not necessarily mean rates facing households and businesses will turn negative. She cites a statistic that at the current bank rate level of 0.1%, the average rate charged on loans to UK households is 2.6%, while the average rate paid on household deposits is 0.2%, implying that being ‘paid’ to take out a loan is a long way off, and that deposit rates could still fall further (albeit by a very small amount) before turning negative.

When it comes to operational issues for banks, responses to the BoE’s operational readiness assessment indicate that negative rates would require system modifications for some banks. For most firms, there are shorter-term tactical solutions that would take up to six months to implement, "typically shorter-term fixes, involving workarounds on the periphery of the core systems, along with overrides in downstream systems and customer communications", the feedback says. "The majority of firms reported that implementing longer-term strategic solutions (permanent changes, involving material systems upgrades that feed through internal systems for managing the calculation of interest, customer communications, treasury, accounting and risk models) would take up to twelve to eighteen months."

No details of why such problems would be encountered were disclosed, but a UK bank CEO, who spoke to The Review on condition of anonymity, says "This isn’t so much of an issue that it will bring the financial system to a halt. It’s more of an issue that you don’t know what you don’t know." They say that banks have been asked to check their operational readiness and complete an audit of systems and test with a negative bank rate, and before they do that, they won't know if it works. "It’s a huge undertaking for banks, not because they think it’s a big issue, but because they simply have to do the work and make sure."

There may also be requirements for banks to update their terms and conditions if negative rates are passed on to the consumer. A possible complication to this would be if legal challenges were to emerge in the UK as they did in Germany. It is also possible that negative rates might require changes to the terms and conditions of wealth managers and platforms, but it isn’t being seen as a likely scenario at the moment.

Implications for advisers

Graham Wingar CFPᵀᴹ Chartered MCSI, partner at Future Asset Management in the UK, doesn’t see a bank rate move into negative territory as a significant pivot point for financial planners, advisers or investors, given that interest rates in the UK have been low for an extended period anyway.

He says: "If the bank rate is +0.1% or -0.25%, that’s just a marginal change and the system of incentives or disincentives from interest rates remains very much the same. We’ve been implementing changes to asset allocations for our clients that are appropriate for a low interest rate environment for years now."

His approach to asset allocation over the past few years has been to create a clear separation in clients’ portfolios between ‘cash assets’ and ‘invested assets’ with higher volatility. The risk profile of the client will determine the bulk of this split. Saving for a deposit on a home purchase within a year or two would lead to a higher proportion of cash, for example, as these clients wouldn’t want to run the risk of a large short-term drop in value.

Graham advises them to keep the cash portion of their portfolio in a bank account, outside of the portfolio managed by him. "It’s not going to give much of a return but there are no adviser fees or volatility, so it’s serving its short-term ‘safe haven’ purpose," he says. "And with yields so low in the closest alternatives to cash, such as gilts, fees are very important to consider. We then have the ability to run the volatility a little higher on the remaining invested assets, in asset classes such as equities, which is that part of the portfolio with a longer-term investment horizon."

"There might be a psychological effect with savers ... if the media starts to mislead people about having to pay to hold savings"

Evidence of UK consumers’ use of cash savings for its safe haven value is borne out in official BoE statistics. Household non-interest-bearing deposits jumped 27% in the 12 months to 31 January 2021, and around 8% in each of the prior two years. But the low interest rate environment, coupled with tax policy, has depressed the cash individual saving account (ISA) market (a cash ISA is a UK tax wrapper whereby £20,000 can be saved each year without any tax being payable on the interest received). The June 2020 HMRC report, Individual savings account statistics, shows that in 2014–15, annual subscriptions into cash ISAs peaked at £61bn. In 2018–19 this dropped to £44bn, with the total amount invested in cash ISAs levelling off since 2015–16 at around £270bn, after a period of continual growth from 2000 to 2015. The fundamental rationale of a cash ISA is now questionable for many. Basic rate taxpayers in the UK do not have to pay tax on the first £1,000 of interest received from savings, meaning that if these savings attracted 0.2% interest, a balance of £500k would be required before any benefit of the cash ISA tax advantage kicks in. A move into negative rates would make this tax advantage even less accessible to savers.

When it comes to borrowing, Graham also does not see much potential for a significant change in behaviour. He says he can't foresee people borrowing more if the base rate turns negative. "That doesn’t mean they’ll be paid to take out a mortgage, just that their existing rate might drop slightly along the lines of the change in the bank rate. Our clients are already borrowing at extremely low rates." He does stress though that his advice to clients is to plan their borrowing around the possibility of interest rates rising, however unlikely that may seem today, to ensure that repayments remain affordable even if rates do rise.

Graham expresses a concern about media and social media hype, even though he doesn’t see negative rates being passed on to depositors (citing the experience of other countries). He says "There might be a psychological effect with savers looking for alternatives to bank accounts if the media starts to mislead people about having to pay to hold savings just because the bank rate turns negative."

The jury is still out on whether negative interest rates have been a success in those countries that have adopted the policy. There is no doubt though, that the impact on financial products and on consumers’ attitudes to the management of their money is significant, although these shifts tend to happen over a period of years, not simply because rates ‘turn negative’. Whether the UK or others will follow suit into negative territory is unclear, but the feedback letter from the BoE suggests that wealth managers, financial advisers and financial planners need to prepare for a further evolution in the environment that affects their clients’ financial affairs.