The Covid-19 pandemic has affected mental health on a global scale. We take a look at some of the data and treatment options available

by Paul Bryant

Visit the CISI Mental Health Portal

The mental health and wellbeing of a population is essential to overall health and work productivity. Mindfulness, as explained in a previous Review article, can be helpful in managing the new set of pressures faced by workers since the Covid-19 lockdowns began. In this follow-up article, we switch focus from individual to global, gauging the scale of the impact of the pandemic on mental health, and chatting to experts about available treatment options.

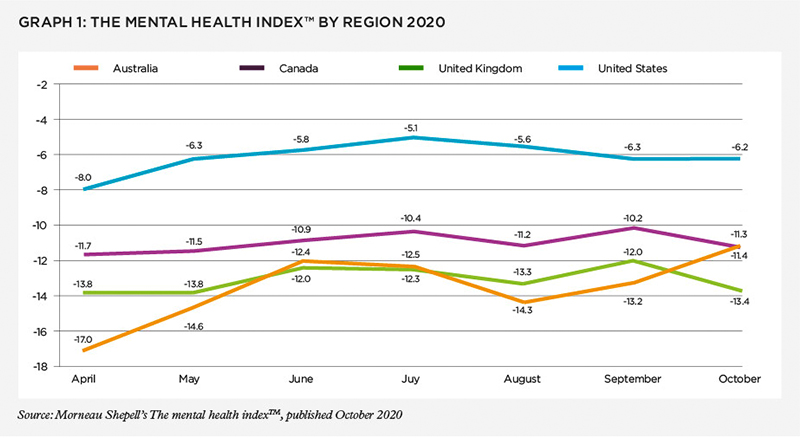

According to the October 2020 Mental health index™ report, a monthly report produced by Morneau Shepell, a multinational provider of human resources and employee wellbeing services, the pandemic has resulted in a significant decline in the mental health of Americans, Australians, Britons and Canadians. Through a series of online surveys of 11,000 employed adults in those four countries, it finds that The mental health index™ score shows a decline from a pre-pandemic benchmark of zero to -13.4 in the UK (the worst affected), -11.4 in Canada, -11.3 in Australia and -6.2 in the US (the least affected).

"The level of mental health in October remains concerning as it indicates that the working population in all four geographies is significantly distressed when compared to mental health scores prior to 2020," the report says.

Canada-based Paula Allen, senior vice president, research, analytics and innovation at Morneau Shepell, explains the significance of this research: "The scale of those declines in Australia, the UK and Canada means that the prevalence of symptoms of declining mental health, such as anxiety, depression, feelings of isolation, and suicidal thoughts, are similar to the most distressed 1% of the population, pre-pandemic." Paula highlights that in the US, although the average decline was not as bad, it is still significant, and that on the east and west coasts, declines have been similar to the other three countries, whereas among the ‘middle-American’ population, the impact of the pandemic has not been recognised to the same extent.

She continues: "The best way to think about these index results is that the pandemic has resulted in a large increase in the risk of poor mental health symptoms occurring, but it doesn’t necessarily mean they will occur. That is impacted by what people do about their state of mental health and the support they receive."

The Morneau Shepell index from September 2020 flags that in all four countries, the most commonly reported top-of-mind issue is the ongoing impact of the pandemic related to finances.

"Like a tsunami building offshore, this mental health crisis has been heading our way globally for a long time"For those who have potentially come into contact with the virus, negative effects can include "post-traumatic stress symptoms, confusion, and anger", according to a review of 24 papers by Elsevier Public Health Emergency Collection on the psychological impacts of quarantine, covering ten countries – Taiwan, Canada, Australia, Sierra Leone, Senegal, South Korea, Liberia, Sweden, US, China – and around 20,000 people, affected by outbreaks such as SARS and H1N1.

The review flags financial loss as a result of quarantine as another stressor. It says this "created serious socioeconomic distress and was found to be a risk factor for symptoms of psychological disorders and both anger and anxiety several months after quarantine".

Dr Becky Inkster, neuroscientist and researcher, honorary research Fellow, Department of Psychiatry at the University of Cambridge, and adviser to several global organisations, including The Lancet Digital Health journal and and some social media platforms, has produced a paper alongside an international team of 179 co-authors – currently under peer review – titled Early warning signs of a mental health tsunami: a coordinated response to gather initial data insights from multiple digital services providers. It is a global collection of data insights from a wide range of digital mental health and wellbeing services that offer a range of support, including patient to clinician communication tools, digitally-enabled treatments, self-managed care solutions and support network communities. It also captures data insights from several financial services providers as well as other relevant sources of data, such as advertising of anti-anxiety medications on darknet markets.

Becky says about the research, "We noticed that for almost all providers, the usage of their resources by those seeking digital mental health support increased significantly during the pandemic." For example, the paper reports that French telemedicine platform Qare saw the number of teleconsultations with a psychiatrist increase by 382% in March 2020 compared to February 2020, and the number of teleconsultations with a psychologist increased by 195% in March 2020 compared to February 2020. Hong Kong-based Neurum Health, a remote patient monitoring platform for people in Vietnam, Singapore, Hong Kong and Mainland China saw a 67% increase in users reporting anxiety in their mood journals between March and April 2020.

"Inpatient beds were converted to Covid-19 units, and outpatient mental health clinics were closed to adhere to social distancing requirements"

Becky points to multiple themes emerging from the data insights provided, such as increased anxiety, feelings of isolation, helplessness, suicidal thoughts, self-harm, grief, bereavement, abuse, sexual exploitation and violence, substance misuse of drugs and alcohol, financial hardship, employment uncertainty and pressures faced by single-parent households.

"In tandem with an increase in seeking support online for mental health issues was a decline in usage of traditional mental health services," says Becky. "Inpatient beds were converted to Covid-19 units, and outpatient mental health clinics were closed to adhere to social distancing requirements," she says. Before the pandemic, there were already "hugely concerning" mental crises emerging. "Like a tsunami building offshore, this mental health crisis has been heading our way globally for a long time. For example, even prior to the pandemic, a World Health Organisation report shared on the Mental Health Foundation website projects that ‘by 2030, mental health problems (particularly depression) will be the leading cause of mortality and morbidity globally'."

The financial services sector hasn’t been spared. According to Alison Unsted, director of strategy and operations at City Mental Health Alliance, a not-for-profit with mostly large UK financial and professional services firms as members: "We saw our members deal with a sudden and huge surge in demand for wellbeing-related services and interventions."

But, says Alison, a huge positive has been that mental health has moved rapidly up the agenda with employers becoming more aware of its impact, support providers adapting to new ways of service delivery, and people having a "new sense of safety to talk about their feelings".

Financial sector feels the stress

Alison highlights some of the sources of stress that Covid-19 and lockdown have had on many in the financial sector, and says that some of these are not always apparent to senior management:

- Working from home can be highly impractical for some, such as those who might be in shared accommodation or don’t have the space to set up a designated workstation.

- People with small children have had to balance a highly demanding job while taking on childcare and home-schooling duties at the same time, without child support.

- Out of sight of management, some have felt the need to be seen to be working hard, so are over-working.

- Finding the balance between work and home life, such as ‘switching off’ after work, has been difficult while being at home full-time.

- Some have experienced problems with loneliness and the lack of social interaction they get at work.

She cites a particularly hard-hitting example of a call centre employee from a financial services company who experienced racist abuse from a client during lockdown. This employee was working from her bedroom, and after the call didn’t have the usual support from a team around her or the opportunity for any sort of debriefing. This can really impact someone’s wellbeing, says Alison.

"It is absolutely clear from the data that people are realising they need stronger financial resilience"

Meanwhile, many furloughed workers have had little or no contact from the workplace, so isolation has been exacerbated, and they can feel of less value to their employers and worried about their job security.

A July 2020 research paper titled Cut hours, not people: no work, furlough, short hours and mental health during the Covid-19 pandemic in the UK by academics finds that people who lost all paid work were twice as likely to fall into an at-risk category for poor mental health, compared to those furloughed or still working any number of hours. The authors mention that a loss of earnings related to unemployment only partly explains mental health symptom changes, and that social connection, having structure and shared goals are also important factors linked with wellbeing.

A last point Alison highlights is that across the sector, access to some treatment and employee wellbeing programmes has been difficult at times, or simply unavailable – such as onsite counselling or gyms: "People couldn’t maintain those ‘protective factors’ and good behaviours."

Coping mechanisms

Coping mechanisms

Advice from Graeme Layzell, a psychotherapist, on how to cope with increased stress:

• Reach out to someone – either friends, family, work colleagues or a mental health professional – to get emotional needs met and to create a support network.

• Get physical (and preferably outdoors because connecting with nature is beneficial to mental health). It could be running, going for a walk, dancing, tai chi, yoga, even singing. As therapists, it’s often what we do with people who have experienced trauma as a way of helping them calm their physical state and quieten their mind. We work hard on calming the physical state.

• Eat more healthily and stay hydrated.

• Get enough quality sleep.

• Give your mind something to do.

• Engage in a hobby, practice mindfulness or meditation, listen to a podcast, or read a self-help book.

Some advice with any of these, particularly the technology-based solutions such as meditation apps, is not to use anything that feels ‘jarring’ to you.

Graeme Layzell, a psychotherapist who works on problems associated with emotional distress with military veterans and people in the workplace, says there’s a lot we can do to deal with the increased stress (see boxout for tips).

Alison explains how employers are stepping up to assist: "Many of our members have focused on increasing the clarity and cadence of their communications, signposting employees to the various sources of internal and external support, and educating them on how to look after their mental health. The more awareness we build around mental health, the more options people will see."

Also, says Alison, many employers now have mental health first aiders available (trained to provide a first level of support, very much as a physical first aider would do). Some have counsellors and psychologists. They have also changed the delivery mechanisms of this support, making much more use of telephone and video technology.

Technology to scale up support

But the use of technology is progressing well beyond that, with screening and support being scaled up through the use of online tools.

Paula Allen says that digital delivery of therapy is not only more widely available than in the past but is sometimes more effective than face-to-face. She says: "You often end up getting to the mental health issue more quickly (for example, there is no therapist-patient small talk or barriers such as embarrassment to overcome); there is less chance of people skipping appointments because digital delivery can be more convenient (it is often available at any time); and a range of therapies can also be delivered (from simple mediation tools to intensive professional treatment) – something that is extremely important if we are going to roll out mental health support on a wider scale."

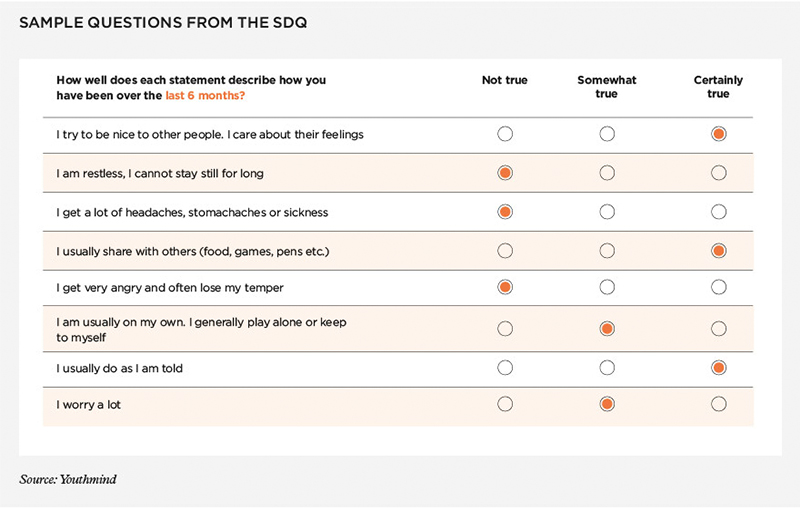

One of these tools is the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ). This was originally designed for use with schoolchildren by Robert Goodman, a former professor of brain and behavioural medicine at King’s College London. But professor Mike Smith of Youthinmind, which owns and operates the SDQ, says it is fully translatable to adults and is an ideal tool to help deal with the surge in mental health problems from the Covid-19 pandemic. The SDQ has been cited in over 5,000 publications globally, many of them academic studies or professional journals.

It is an online questionnaire that takes between three and five minutes to complete.

Mike says the output is "highly suggestive" of specific issues, but not an actual diagnosis: "This is an at-scale filter that suggests when professional help is likely to be needed and also gives professionals an initial insight into potential problems. It provides them with lines of enquiry. Also, follow-up assessments can be used to give clinicians insight into how patients are responding to therapy."

The SDQ scores on five dimensions: emotional symptoms; conduct problems; hyperactivity or inattention; peer relationship problems; and impact. Each individual score as well as the total score contributes to providing insights into the mental health condition of the questionnaire-taker.

Mike describes a simplified example: "If someone has a high ‘impact’ score, but a total score and all other dimensions that are not unusual, the clinician would not be looking to address emotionality or reducing this person’s emotional response to situations, but rather how this person reacts to having those emotions – the ‘impact’ of them. If they are feeling fearful, say about contracting Covid-19 when returning to work, that’s fine. But if that means they refuse to go to work, as opposed to just being very careful when they return, that’s not fine and needs to be addressed."

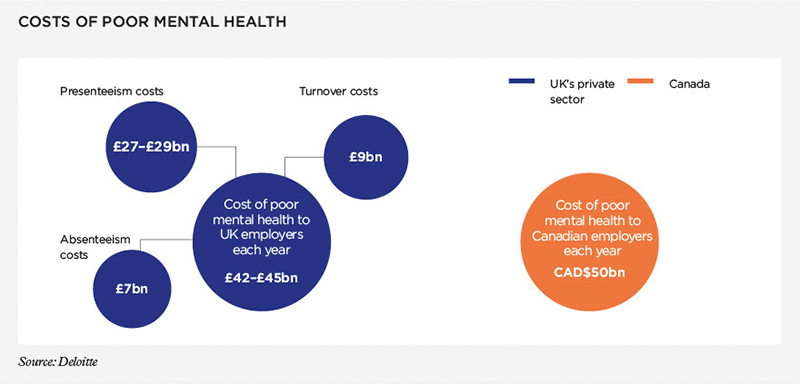

Mike is keen to see the SDQ rolled out across many workplaces. He says: "I think it is fairly obvious that the mental health of employees should be a legitimate goal of any business. The costs of poor mental health are enormous, such as a loss of productivity, or even suicide."

Data sourced from two Deloitte reports: Mental health and employers; and ROI in workplace mental health programmes

Employers interested in making the SDQ available to staff can get in touch with Mike at Youthinmind, but they need to think through issues such as dealing with privacy and the potential stigma attached to taking a mental health questionnaire. Employers could, suggests Mike, make it available as a social benefit to employees, who can use it themselves and with their families.

Becky Inkster says that during the pandemic, digital technologies have become a major route for accessing remote care. However, "There is a huge range of options available but the need to ensure that these tools are safe and effective has never been greater," she adds. In a call-to-action paper on Covid-19 and digital mental health that Becky wrote with colleagues, they raise five calls to action to ensure the safety, availability, and long-term sustainability of digital technologies in mental health.

"We’ve seen a new sense of community and showing care for one another. I hope we don’t lose that""First, due diligence: remove harmful health apps from app stores. Second, data insights: use relevant health data insights from high-quality digital tools to inform the greater response to Covid-19. Third, make high-quality digital health tools available without charge, where possible, and for as long as possible, especially to those who are most vulnerable. Fourth, transform conventional offline mental health services to make them digitally available. Fifth, encourage governments and insurers to work with developers to look at how digital health management could be subsidised or funded," she says.

Financial companies, and financial advisers in particular, should also be aware of their (perhaps larger than expected) role in the mental health of society going forward, says Paula. She says that a key message from The mental health index™research is how important financial wellbeing is. "It is absolutely clear from the data that people are realising they need stronger financial resilience. And what we have seen is that when people have taken action with respect to their finances, such as creating a savings nest-egg, their mental health has improved. Even just understanding their financial situation and removing some uncertainty has a positive impact, which is obviously the domain of financial advisers. I would say the sector has a key role to play in our recovery from a mental health point of view," she says.

Alison is hopeful that in the wake of the pandemic we should be in a better place to deal with mental health. She says: "There is a renewed sense of safety to talk about our feelings, and a real sense of being able to be your whole self with work colleagues, with children regularly appearing in the background of Zoom calls. We’ve seen a new sense of community and showing care for one another. I hope we don’t lose that."