On 5 December 2018, our Wealth Management Forum hosted a debate on the effectiveness of regulation. Committee member Clive Menzies, Chartered FCSI, coordinator of the MacroRisk Connect Programme, expands on the case put to oppose the motion

Before the debate commenced, 68% of the audience agreed with the following motion while 32% disagreed:

This house believes financial services regulation has made the world a safer place for investors.

Big Bang changed the game

To answer the question in the title, we need to go back to before implementation of the Financial Services Act 1986, which came to be known as Big Bang, when the old self-regulatory structure of the UK Stock Exchange was swept away on 26 October 1986.

Prior to that was a self-regulating, distributed network of independent players, all operating under personal, unlimited liability in a single capacity or function. There were stockjobbers who made markets in quoted securities and stockbrokers who mediated between the jobbers and market customers, ie. traders and investors. In primary markets, merchant banks, who typically initiated merger and acquisition transactions and created securities to raise capital, similarly operated under unlimited, personal liability.

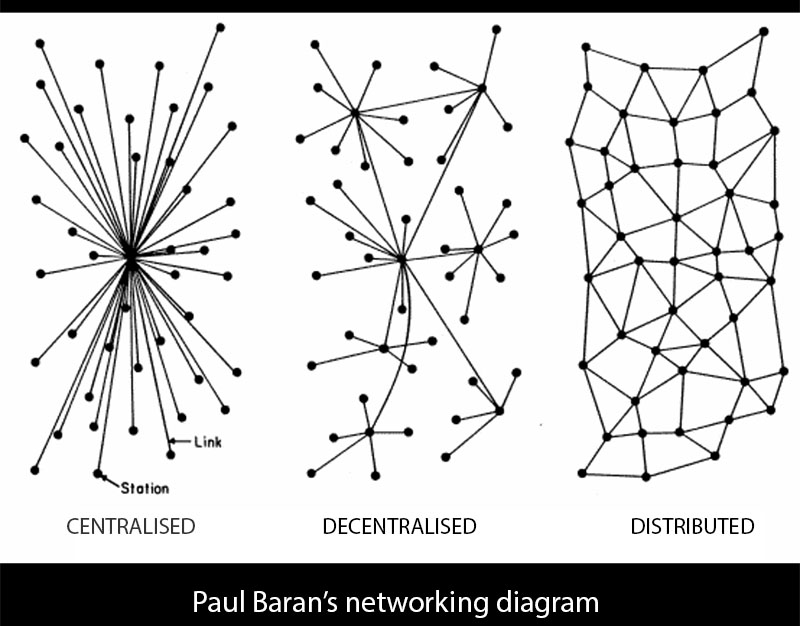

In 1986, Big Bang removed personal liability and scrapped single capacity, leading to concentrated market power. Former merchant bankers, stockbrokers and jobbers were bought out and went to work for the global banks, which acquired their firms and many important ancillary activities. Big Bang eliminated the distributed network of mainly autonomous, independent players, as shown on the right of the illustrative diagram below, to concentrate power, as shown on the left.

‘Too big to fail’ global banks emerged through acquisition of most of the independent players. They dominate the web of power, which extends into every aspect of financial services to ensure their interests are protected and served. When we refer to the markets, we imagine that prices and indices reflect the accumulated thinking of many independent participants. The reality is different.

In financial services and many other regulated activities, fixed, written rules and regulations attempt to apply a permanent, one-size-fits-all policy framework to a system of highly complex, nuanced, fluid, ambiguous transactional and fiduciary relationships which are constantly evolving. The rules and regulations become the arbiter of behaviour, removing responsibility from the parties to those relationships for their morals and behaviour.

In the UK, post Big Bang, City culture moved from financial services practitioners considering the interests of their clients and themselves to considering what they could get away with.

Those who were schooled in the old, self-regulating system are now fast disappearing. Soon, there will be little memory of how effective the system, which applied rules and regulations within a hierarchical structure, was. Power was much more diffuse and posed little systemic or macro risk. But it wasn’t perfect.

Pre-Big Bang, distributed self-organisation was effective in policing financial services within ‘circles of trust’ based on a shared understanding of a common code of behaviour. There was the odd scandal but the system was reasonably successful in keeping the majority honest, through self-interest, and there was an absence of systemic or macro risk arising from scale, homogenisation and virtualisation of securities which are the primary financial/economic threats we face today.

The rise of money powerIn the post-Big Bang world of centralised money power, we have created inevitable consequences: manipulated markets, totally ignored by statutory regulation, and systemic or macro risk.

We all share responsibility for how the markets have evolved. Those who went to work for the global banks were amply rewarded and most were oblivious to how they became complicit in the creation of an uncontrollable monster in the form of centralised money power. This situation has much less to do with the will of those at the top of the pyramid of wealth and power, than the structure itself, which is driving attitudes and behaviour through incentives and penalties, while keeping information siloed so that few can see how the political economy works or how its dire consequences are related/caused.

Increasing scale of corporations and concentration of activities into ever larger organisations, both public and private, has created asymmetric power within and across markets and the political economy, leading to global, systemic risk. Regulation is often the fig leaf of control applied to ensure these large organisations perform as intended, but the regulatory frameworks are captured by the very monopoly of power they ought to regulate. Regulation is one lever of power through which concentrated, asymmetric power is exercised. Nowhere is this more significant nor apparent than within financial services.

Who controls world trade?

A study published in New Scientist reveals that through a network of common directors and shareholdings, a ‘super entity’ of 147 global corporations control 40% of 43,060 transnational corporations (TNCs) and 60% of their turnover. Circumstantial evidence suggests that those 147 corporations are much more tightly held behind a facade of agents, nominees, trusts and foundations.

Global banks feature prominently in the top twenty of the 147 and 45 of the top 50 are financial corporations.

Central banks are the centre of money power

Michael Howell at Cross Border Capital has been tracking central bank balance sheets and capital flows against market indices for three decades and notes a distinct correlation between central bank interventions and major market trends.

The effect of market interventions by the Fed and ECB on the S&P500 from mid-2008 to 2012

Source: www.pretzelcharts.com

The S&P500 peaked in the autumn of 2012 at around 1450. The index doubled to its record high in January 2018 of 2940.91. Most of the major market rises are pre-empted by central bank buying but once the central banks desist, reality begins to be reflected in market prices as they tend to level off or fall until the next intervention begins.

Sooner or later, like all good things, this liquidity fed bull market will come to an end. The more a bubble is inflated, the louder the bang when it pops.

Systemic crises

Each time history repeats itself, the price goes up - Ronald Wright, A short history of progress

Central banks are privately owned by the same interests that control the global banks. Most of the world’s central banks are under the control of the privately owned Bank of International Settlements (BIS) and its recently created associate, the Financial Stability Board (FSB), chaired by Bank of England Governor, Mark Carney. The US Federal Reserve Board (Fed) is no more federal than Federal Express. The Fed comprises 12 privately owned, regional, federal banks. This model is replicated across the world.

A year after Big Bang came the first wake-up call to the systemic or macro risks building in the markets, in the form of the 1987 market shock. Fed chair, Alan Greenspan’s response was the ‘Greenspan put’ – visible central bank intervention to support the markets.

In 1995, confidence in the system was again shaken, by the collapse of Barings under the weight of £827m of trading losses incurred by a ‘rogue’ back office trader in the bank’s Singapore office, Nick Leeson. Before dismissing this as just a rogue trader, think about the possibility of such a loss occurring under the pre-Big Bang, self-regulatory regime guaranteed by unlimited, personal liability. The principals of Barings would have understood every aspect of their business and it is unlikely they would have sanctioned either the magnitude or the delegation of authority to allow such transactions as those which bankrupted the bank.

Regulation is often the fig leaf of control applied to ensure large organisations perform as intended

If Barings was the second wake-up call, the collapse of Long-Term Capital Management (LTCM) in 1998 should have prompted a deep inquiry into the systemic or macro risk arising from scale, homogenisation and financial engineering. Although the headline cost of resolving the LCTM crisis was ‘only’ US$3.5bn, the real cost is arguably much greater if the impact of contagion is included.

Yet in the forward to the celebratory report of 2006, Big Bang 20 years on, Nigel Lawson claims: “It is clear that the reforms triumphantly succeeded in achieving their objective.” Conventional wisdom decreed the system was working well.

Meanwhile, pressures had been building in a corner of the derivatives market since 2000, following the dotcom bubble collapse of that year, unnoticed by regulators and most others. There was something of an alarm bell in January 2008 when Jérôme Kerviel lost Société Générale €4.9bn but the sub-prime mortgage and derivatives markets, which had seen phenomenal growth over the preceding eight years, exploded into global consciousness in September of that year.

When we talk about history repeating and the price going up, we were totally unprepared for the staggering cost of the sub-prime crisis which is arguably still being paid today, not by the culprits, but by the rest of us, including many working in financial services.

According to an audit report, the US Fed gave some US$16tn to global banks over two or three years following the crisis. In addition, we’ve had quantitative easing (QE) by the Bank of England, US Fed, ECB and BoJ. QE has driven asset prices to unprecedented levels.

Sub-prime crisis

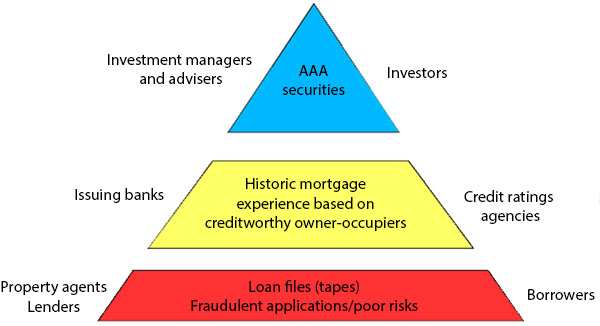

Structural incentives obscured the toxic nature of mortgage backed securities and their derivatives, fuelling the sub-prime bubble. Regulation failed to identify or address the problem because of the compartmentalisation of functions and responsibilities within large scale organisations, giving rise to a total lack of accountability within the system that created the toxic sub-prime securities and their derivatives.

Until the 1970s, investors delegated due diligence to credit rating agencies, for which they paid a fee. When rating agencies started charging bond issuers for ratings, their financial interests converged. Investigations following the crisis revealed evidence of collusion between issuing banks and rating agencies, optimising risk profiles of securities to achieve AAA ratings. In some cases, credit raters had no access to the underlying mortgage data which contained fraudulent applications and loans to house buyers with insufficient earnings. Consequently, they applied ratings on the basis of historical mortgage data from an era when loans were only granted to creditworthy owner-occupiers.

Financial incentives obscured the true nature of the sub-prime debt instruments:

- Buyers and property agents gained in a rising property market.

- The original mortgage lenders profited from loose underwriting of dubious loans which were sold on to the banks issuing sub-prime mortgage debt and derivatives.

- Issuing banks earned securitisation, underwriting and other fees while trading their own book, sometimes at their clients’ expense.

- Rating agencies enjoyed a fourfold increase in revenues from 2000 to 2007.

- Investors bought AAA securities at exceptional yields.

Had all participants been held personally liable for their actions, each would have conducted their own due diligence, rather than abdicate responsibility to others who were incentivised to lie and penalised for exposing the truth – see The big short by Michael Lewis: those betting against the sub-prime market were being squeezed by the banks in spite of the accumulating evidence that the securities were fraudulently overpriced.

In an unlimited liability environment, the sub-prime market wouldn’t have thrived but withered due to lack of interest, if it ever emerged at all – there wouldn’t have been sufficient reward to justify the risk.

Systemic or macro risk

In short, regulation seeks to find ‘bad apples’ in a contaminated barrel which creates bubbles and collapses. The financial markets are structurally flawed and contaminated; policing individual instances of wrongdoing is never going to address systemic or macro risk arising from:

- Scale – asymmetric power ensures the dominance of the ‘short side’. See point 3 of ‘Shifting from central planning to a decentralised economy’ by Richard Werner: “Markets are never in equilibrium, thus don’t be fooled by prices, but consider quantities: The short side exerts power.”

- Homogenisation – commercial and regulatory pressures funnel capital to the global banks and into their products, creating a ‘winner takes all’ environment in which personal accountability has been removed. Buy lists and model portfolios have become de rigeur to comply with regulation and maximise profit – those that don’t emulate or buy into the ‘market leaders’ and their process/research/products find it hard to compete.

- Virtualisation – a vast proportion of securities traded are virtual or financialised, ie, ‘paper’ representing assets, not the assets themselves. Estimates vary but one study suggests that the derivatives market adds up to some US$700tn. Netting off would reduce that figure but nevertheless, it is a ‘known unknown’ in terms of the risk within the derivatives market.

A recent study suggests that for every ounce of physical silver, some 517 ounces are traded in the form of ‘paper’ (derivatives) – more than double that of gold, with corresponding figures of 233 paper ounces traded for every ounce of physical gold. Sub-prime mortgage backed securities and their derivatives were multiple paper (or more accurately, computer simulations) representations of overpriced assets constructed from fraudulent mortgages.

Since 2008, little has changed in terms of a systemic response to address the problems of scale, homogenisation and virtualisation, all of which are arguably worse than before the last crisis. What will trigger the next crisis is hard to predict but the derivatives markets are the most likely candidate. Irrespective of the trigger or perceived cause, the fundamental driver of markets is bank credit or debt and the credit cycle seems to have turned. We are already witnessing global market and economic discomfort.

Caveat emptor – let the buyer beware

So what should we do?

We have been subtly steered away from attitudes, customs and norms which governed human behaviour and relationships for millennia into a state of trained dependency on authority or centralised power. This is a societal problem which has serious ramifications across the political economy but, specifically within financial services, buyers are no longer responsible for their decisions, nor are they responsible for deciding whom to trust.

Buyers abdicate responsibility to regulation to conduct due diligence while advisers, agents or sellers are no longer held personally accountable for their actions. The claim, as within so much of the political economy, is that we should trust in authority (specifically the FCA in the UK) to protect our interests. It hasn’t, it won’t and furthermore it can’t.

Which is why, when some of this information was revealed in the case against the motion – This house believes financial services regulation has made the world a safer place for investors

– 18% of the audience, who had previously agreed with the motion, changed their minds.

The final vote, at the end of lively discussion and final summations from both sides, was 50/50.

One of the reasons that more didn’t switch their vote is because the information, presented in this article and in opposition to the motion, is so alien to our common understanding that we are reluctant to give it credence. Our world views have been embedded over years of training by authority to adhere to ‘accredited’ (authorised) sources of information, within defined boundaries to our learning, so that our perceptions are blind to the wider and deeper reality.

Decentralise

The research and analysis on which opposition to the motion and this article are based were facilitated by self-organised, co-creative learning over a period of seven years. If we want to understand how the world works, we need multiple perspectives to see the whole political economy and how the components interact. Self-organised, co-creative learning is the most efficient and powerful means to sift, analyse and synthesise sufficient depth and breadth of diverse information and analysis to develop a shared understanding of the political economy.

Co-creative learning will reveal how best to revert to distributed power within financial services while those whose livelihoods disappear through decentralisation can, by the same means, develop an understanding of how their talents and energy can be best employed for their own benefit, that of their families, communities and for the benefit of the wider world beyond.

The political economy and financial services are too big and too complex to be planned or managed. They are constantly evolving, which renders them impossible to frame and monitor within the context of rules-based regulation. However, they can self-organise and self-regulate.

In summary, self-regulation based on unlimited liability, single capacity and caveat emptor will dissolve centralised power into a distributed market economy and, unlike statutory or any other form of rules based regulation, will make the world a safer place for everyone.

Information on the free, open source CoCreative Learning project is available at cocreativelearning.org.

Views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and do not necessarily represent the views of the CISI.