For someone who left school at 16 because he needed to find a job, Steven Cooper has made a remarkable success of his career. Having joined Barclays in an entry role doing administrative tasks – “I was promoted to a cashier, that’s how junior I was,” he says – his potential was soon spotted and he was one of the first four non-graduates to be enrolled on the bank’s graduate programme. Steven subsequently rose through the ranks over 30 years to become Barclays’ chief executive of personal banking across the UK and Europe and chief executive of Barclaycard Business.

Today, he’s in the top job at private bank C. Hoare & Co and is one of the commissioners on the Social Mobility Commission – a government-appointed advisory body – a position from which he’s able to play an instrumental role in promoting opportunities for young people from similarly disadvantaged backgrounds to his own.

Reflecting on the challenges he faced in his own career, Steven says: “One was my own lack of confidence. I hadn’t developed the confidence you get at a private school, or from university, or the social network that comes with a certain type of privileged background.” He also suffered from not having the career development structure that many of today’s potential leaders can take for granted. “Today, organisations that are progressive in developing talent will put in place a structured programme to ensure people get the breadth of experience they need, the knowledge and skills to be the best they can be, and to become future leaders of the organisation,” says Steven.

The CISI believes that professional bodies can play an important role in promoting the agenda of social mobility, both in financial services and elsewhere

As his career progressed, Steven “felt occasionally there was a glass ceiling,” and had the sense that he was being looked down on because he “didn’t have a certain level of education”. But, on the positive side, he also became acutely aware of how big a difference help and support from others in the organisation could make.

A vital issue At a time when there is growing polarisation of wealth in many countries, including the UK, as evidenced by the World inequality report 2018, social mobility has become a vital issue for governments and other policymakers, and one that employers are increasingly recognising they need to get to grips with.

There’s no universally accepted definition of social mobility, but in colloquial terms it is widely understood to mean the ability of people to improve their socio-economic circumstances, or to move up the social ladder. The UK government defines social mobility as “the link between a person’s occupation or income and the occupation or income of their parents. Where there is a strong link, there is a lower level of social mobility. Where there is a weak link, there is a higher level of social mobility.” It can also be seen as a measure of the degree to which any society is meritocratic.

The issue of social mobility is now gaining traction among many leading organisations. The Social Mobility Employer Index, inaugurated by charity the Social Mobility Foundation (SMF) in 2017, has seen participation from 172 UK employers representing more than 1.5 million people, and expanded from ranking the top 50 to the top 75 employers in 2019.

Financial services Around 41% of employees in financial services have parents working in the same sector – more than three times the national average of 12% across other sectors, according to widely reported research from KPMG in April 2019. In insurance, more than half of workers have followed their parents into the sector.

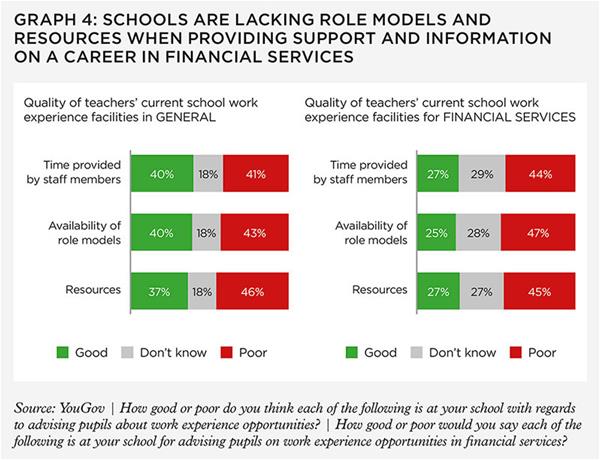

As part of a wider research project on social mobility, the CISI recently commissioned research from market research and data analytics firm YouGov, looking at how parents and teachers view the importance of work experience, particularly in relation to their children/charges gaining employment in financial services. Of the 513 primary and secondary school teachers, and 1,013 parents in total that responded, the research finds that 77% of parents with children at independent schools feel their child is aware of financial services as a career path, compared to 50% of those with children at a local authority school.

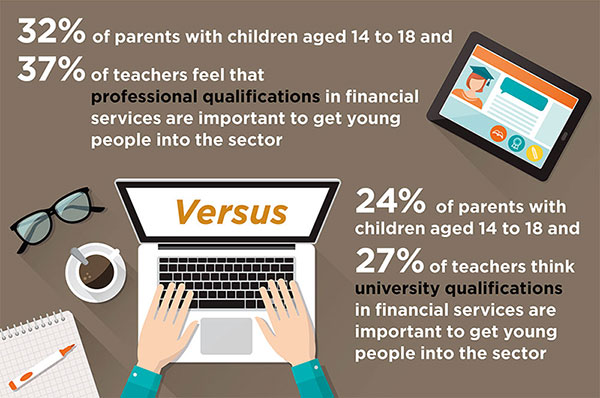

The CISI believes that professional bodies can play an important role in promoting the agenda of social mobility, both in financial services and elsewhere. The research mentioned above shows that 45% of parents with children in grammar schools believe having good contacts and connections is key to getting into the financial services sector. Interestingly, both parents and teachers think professional qualifications in financial services are more important than university qualifications in financial services, with 32% of parents with children aged 14 to 18 and 37% of teachers feeling that professional qualifications are important, compared to 24% and 27% respectively for university qualifications.

Membership of organisations like the CISI provides an essentially meritocratic approach for those who want to pursue a career in financial services, with more senior membership status awarded to those who sit higher level exams. Susan Clements, CISI global director of learning, says: “The brightest and best don’t always enter the workplace with a traditional academic pedigree. Vocational qualifications are an efficient and effective way for anyone to earn while they learn’, enabling them to progress and reach their full potential within the financial services sector. Membership of a professional body provides recognition and an opportunity to build and maintain a network of useful contacts.”

Mixed picture David Johnston, the former chief executive of the SMF (he stood down at the end of 2019), says that, overall, the financial sector presents a “mixed picture”. Retail banks, for example, which have traditionally recruited locally for their high street branches, have less of a problem, while in contrast some of the more niche areas such as private equity and asset management have less of a track record for hiring and developing people from diverse backgrounds. Investment banks, he says, are making efforts, but while J.P. Morgan is the standout at number 17 in the SMF Index, others have tended to import a model of diversity from the US that focuses primarily on gender and ethnicity.

Accountancy firms, on the other hand, have a strong record to show on social mobility, and two firms in particular, KPMG and PwC (see case study), have topped the SMF ranking.

Steven Cooper says that “at one level, financial services is doing exceptionally well and better than most other sectors”. He believes that the sector can claim a strong record on providing apprenticeships and reaching out to disadvantaged communities to help people with different aspects of job hunting, as well as developing basic financial literacy skills.

Case study: PwC

PwC, ranked as the leading employer in 2019’s Social Mobility Foundation Employer Index, has a dedicated team working on social mobility. It is involved in outreach within schools and communities as well as recruitment.

In 2017, the firm decided to make a difference in one community and became the cornerstone employer for the Bradford Opportunity Area (OA), the largest of the 12 'opportunity areas’ – areas of the country where social mobility is lowest – identified by the UK government nationally.

In 2019, PwC opened an office in Bradford, which now employs 135 people, many of whom are drawn from the local community. The firm has also pioneered a paid work experience programme aimed at underprivileged students in Year 12, with a national target of offering 1,000 places to disadvantaged students in the five years to 2022.

PwC is a strong believer in setting targets and measuring progress, which is published via a scorecard in its annual report. For example, it aims to bring the proportion of new hires who received free meals at school – in England and Scotland, children in Year 3 and above are entitled to free school meals at state-funded schools if their parents receive state benefits – up to the national average, which is approximately 15%. The base year was 2015 at 6% and that has already risen to 10%.

The CISI is actively involved in outreach programmes to help promote upward social mobility in financial services. Since September 2013, it has been sponsoring teachers in Liverpool, Manchester and London, via its Educational Trust, to deliver its level 2 and 3 foundation qualifications to sixth-formers in disadvantaged areas in these cities.

Matthew Bolton, CISI teaching and learning specialist, says: “As part of these educational programmes, students are also provided with mentoring, work experience placements and the opportunity to develop their employability skills, all with fantastic support from members in our regional committees. The aim has been to develop the next generation of professionals by providing them with the baseline knowledge not traditionally taught in schools and colleges, as well as opening doors to careers that these young people may not have been aware of or felt were out of their reach. So far, we have reached over 400 16 to 18-year-olds in these areas."

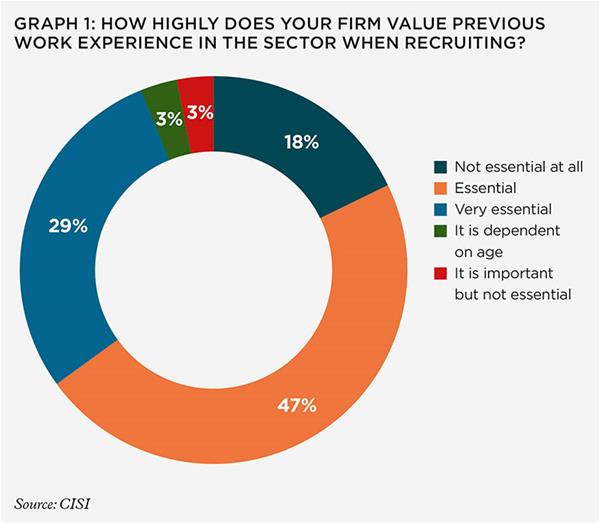

Research by the CISI also explores financial services firms’ attitudes towards work experience. At the time of writing, responses are still coming in, but preliminary results from around 40 firms show that work experience is a key factor that firms consider when recruiting. Firms were asked how highly they value previous work experience in the sector when recruiting. Some 47% say that previous work experience is 'essential’, while a further 29% believe it to be ‘very essential’. In contrast, just 18% of firms think it’s ‘not essential at all’.

Greater imperative Financial services arguably has a greater imperative to deal with social mobility than other sectors. Among the public at large, many blame the banks for having triggered the financial crisis, an event that led to austerity and further setbacks for already disadvantaged communities. Access to finance and financial products is also key to achieving social mobility, while lack of access to a bank account is seen as a characteristic of deprivation.

In 2018, the Open University Business School’s True Potential Centre for the Public Understanding of Finance published A review of social mobility in financial services. Liz Moody, one of the authors of that paper, says: “Financial services is more prominent than other sectors in terms of its influence on our economy. And the number of people employed in financial services is significant. When things go wrong with financial services, if we have a banking crisis or a breakdown in technology, it’s serious. If people can’t access money and credit, that has an impact on social mobility.”

According to data from TheCityUK, the sector employs 2.3 million people across the UK. Financial and related professional services accounts for £11 in every £100 of tax paid to the exchequer and is the generator of the largest trade surplus of any UK sector: £60.9bn in 2017.

Yet, in the UK, work placements were removed from the curriculum for Key Stage 4 pupils (usually aged between 14 and 16) in 2012 after a recommendation in the 2011 Wolf review of vocational education. The report said the education system should instead focus resources on providing longer internships for older pupils over the age of 16.

Research by the Career Colleges Trust, published in February 2018, finds that of the 1,000 14 to 19-year-olds asked, the vast majority (83%) would like work experience to be part of their education, and the call for work experience to be reintroduced has been echoed by bodies such as the Federation of Small Businesses in April 2019. The CISI-commissioned YouGov research clearly shows the potential of work experience to promote social mobility, with a fifth of parents saying that their first job was in the same sector and influenced by their work experience.

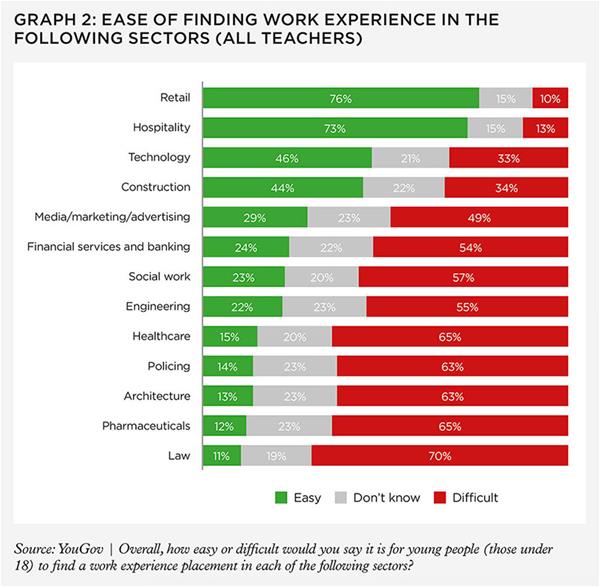

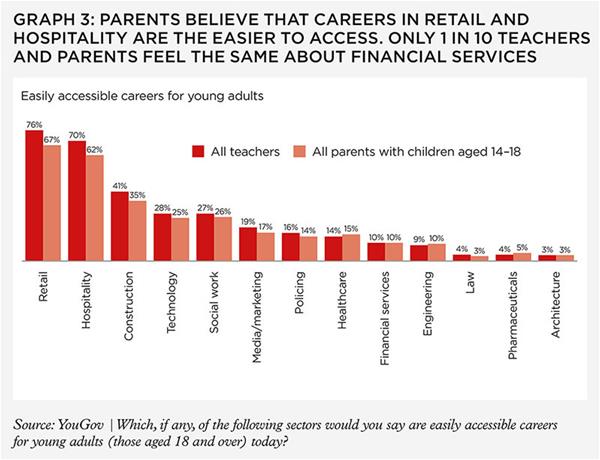

The YouGov research reveals that 75% of teachers and 65% of parents say they would support the compulsory reintroduction of work experience. Financial services ranks in the middle of sectors for ease of obtaining work experience, but only one in ten teachers and parents believe that careers in financial services are easily accessible.

Liz says that as well as developing products that are inclusive, diversity in employment practices is crucial to maintaining the public’s trust. She believes that diversity of backgrounds and experience can bring in different values and change the worst aspects of the culture in financial services. “It might reduce the groupthink that got us into the banking scandals and the financial crisis,” she adds.

David Johnston concurs: “There are plenty of fairness arguments, but we think you should do this because you can get better people – after all, how could all the best people possibly come from a tiny number of schools and universities? But, also, by having people from diverse backgrounds, you can attract different customers and enter different markets in a way your traditional colleague may not be able to help you to.” A 2016 article in Harvard Business Review surveys evidence from numerous studies to show that different kinds of diversity, including race, gender and culture, lead to better performance.

Practical measures For employers, what does promoting social mobility mean in practice? It is often framed primarily in terms of recruitment practices – the academic backgrounds and specific universities that firms hire people from. “In the first year we did the Index, we found that employers visited Oxford and Cambridge more times than the 110 other universities combined,” says David.

As well as broadening the range of universities they recruit from, companies are encouraged by the Social Mobility Foundation to remove filters such as UCAS points – a number which indicates qualifications grades for aspiring university students – from their initial screening of applicants and, more importantly, to introduce alternative routes to employment for candidates who prefer a more hands-on approach to career development, such as through work experience and apprenticeships.

Some companies are even developing artificial intelligence-based systems that can predict how well somebody will perform in the job, which is seldom down to academic qualifications. IBM’s Watson Recruitment solution, for example, claims to be able to identify high-potential candidates by matching against key success profiles, “surfacing candidates who may have been missed by recruiters, thus eliminating any steps in the search process that may have introduced unconscious bias”.

But it’s not just about hiring people from different backgrounds, it’s also about enabling them to break through the ‘class ceiling’ and progress at the same speed as those who’ve come through the more familiar and trusted route – “getting on” as well as “getting in”, as David puts it.

Collecting data If companies are to make serious inroads on social mobility, they need to first have awareness of the issue, then to understand what it means for them, says Steven. And key to that is collecting data. “Few businesses in reality collate information on the socioeconomic backgrounds of their people,” he explains. “How do you understand what data you need, what questions you need to ask? And how do you give confidence around providing that information, for example, in terms of the General Data Protection Regulation?” Steven says that collecting this data is important so firms avoid what he calls “an unconscious biased filtering process” – in other words subconsciously favouring people from particular backgrounds over others from differing backgrounds.

One way to tackle this could be through ‘reverse mentoring’, which, according to a Harvard Business Review article, pairs junior employees with senior employees, with the latter benefiting from the former’s worldview and skillset.

Social mobility matters, says Steven, because nobody should be limited in terms of opportunities because of the circumstances in which they were born. Giving a chance to young people from underprivileged families or those with no working role model has one other bonus, he says. “It’s a far more enjoyable day job if you connect with people who are very different from you, and you learn and grow with each other.”

The full article was originally published in the February 2020 print edition of The Review.

The full print edition PDF is now available online for all members.

All CISI members, excluding student members, are eligible to receive a hard copy of the quarterly print edition of the magazine. Members can opt in to receive the print edition by logging in to MyCISI, clicking on My account, then clicking the Communications tab and selecting ‘Yes’.

Once you have read the print edition, keep coming back to the digital edition of The Review, which is updated regularly with news, features and comment about the Institute and the financial services sector.