The taxman took a record £5.2bn in inheritance tax (IHT) in the year to April 2018 – an 8.1% increase on the previous 12 months, according to

figures from HMRC.

Death is proving an increasing source of income for the government but given the complexity of the rules and the frequency with which these change, it is becoming ever harder for individuals to navigate estate planning.

It is also more important than ever before to have a succession plan. Improving life expectancy has seen the number of three- and sometimes four-generation families increase, meaning estates may need to cover not just children and grandchildren but even great grandchildren too, according to the Government Office for Science’s 2015 paper,

Intergenerational relationships: Experiences and attitudes in the new millennium.

Sharing wealth by giving it away is relatively easy but not only does this attract IHT if done within seven years of death (the seven-year rule), it also sees the individual lose control of the assets. To counter this loss of control, trusts allow people to bequeath wealth outside of the taxable estate while setting rules for how and when the assets are passed on.

However, they are not free from IHT and any assets put into the trust in excess of the nil rate band are generally treated as a chargeable lifetime transfer – the rate at which charges start to apply, which is frozen at £325,000 until 2021 – and taxed at a rate of 20%.

If the settlor dies within seven years of the transfer, there may be additional IHT to pay, subject to whether any reliefs, for example business property or agricultural property relief, are available.

The trust will also incur a ten-yearly IHT charge, which can be complex to calculate, and there are exit charges of 6%.

The ten-year charge is calculated using a standard formula that is capped at 6% on the value of relevant property in the trust. Where available, business property relief and agricultural relief are deducted. The resulting charge is then reduced by the nil rate band in force at the ten-year anniversary minus any chargeable lifetime transfers made by the settlor in the seven years before establishing the trust. Any distributions made by the trustees prior to the ten-year anniversary are deducted. Once the exact rate has been determined, it will be applied to the current value of the relevant property held in the trust. Where the value of the trust assets grow, there will be increased ten-year IHT charges. The trust ten-year charges are broadly supposed to be the same as a ‘generation’ of IHT, that is 6% every ten years six to seven times, broadly equating to 40% on death.

How family investment companies workThere is an alternative. Solicitors and accountants are seeing an increasing interest in family investment companies (FICs), which offer tax efficiency to those wanting to pass wealth on without losing control over how the assets are managed.

Helen Cox, managing associate at law firm Mishcon de Reya, says clients recognise that the tax advantages of trusts “aren’t what they used to be” and the demand for FICs has grown as a result.

A FIC is generally a UK-based company created for wealth and succession planning. It can be set up on a limited or unlimited basis. Depending on the client’s circumstances, the use of a non-UK incorporated company, which is managed and controlled in the UK (so a UK tax resident) should also be considered.

The requirements for a small limited company with a turnover of less than £10.2m and fewer than 51 employees are relatively minimal. The company owners simply need to file abridged accounts or a directors’ report and there are no audit requirements. This helps to make things less complex to set up, and has lower ongoing costs than larger companies, so is more manageable and attractive for potential investors.

The FIC – which can hold pretty much anything from cash to property and shares – has bespoke articles of association which determine how the company will be run and who is entitled to what. The articles set out multiple classes of shareholder. Typically, the person setting up the company has voting rights and control over the day-to-day running but receives no paying dividends. The beneficiaries meanwhile receive economic shares but limited voting rights.

Numerous advantagesThe benefits to setting up a FIC are numerous, according to Helen.

First is taxation. The cash contributions, shares from an existing company and loans made to the FIC by the founder are not considered a transfer of value for IHT purposes and these funds can be extracted from the company later, tax free. Cash is perhaps the easiest contribution families can make to an FIC. Similarly, giving children non-voting shares is not seen as a gift and is therefore not subject to the seven-year rule, or any IHT charges. There are, however, complex anti-avoidance ‘settlements provisions’ that do need to be considered on a case-by-case basis.

The same is not true of property however, which is seen as a transfer of value and will face an IHT charge if made within seven years of death. The disposal is also subject to capital gains tax (CGT).

The FIC’s income (but generally not dividend income) and capital gains will be subject to UK corporation tax, which is currently 19% but scheduled to fall to 17% in April 2020. The FIC directors can accumulate income, which is then distributed via dividends. However, the tax-free allowance for dividends changed in April 2018 from £5,000 to £2,000, after which recipients are subject to a charge based on their tax band.

This compares to trusts that Helen says “are immediately taxed at a rate of up to 45% on income and up to 28% on capital gains”. This is on top of the ten-yearly and exit inheritance tax charges already noted.

However, Emma Hendron, partner at chartered accountancy firm Saffery Champness, says: “While there may not be immediate IHT charges, the value of the FIC will be within the scope of IHT, although it may be possible for the value of future growth to be given away. There are complex settlement anti-avoidance rules that need to be considered. Also, the FIC can provide tax deferral but there are two layers of tax – corporate, at a lower rate, and personal tax on the extraction of profits other than by repayment of the loan. It is also worth noting that it is tax inefficient to use a company for significant capital gains."

Next is asset protection. As noted, the ownership structure allows the founders of the company to decide how and when any wealth is passed to shareholders. This is particularly useful in the event of family break up since the articles of association set out who is entitled to what. “This can provide peace of mind that wealth will only transfer with agreed family consent,” Helen says.

The FIC also provides a familiar, simple structure in comparison to the complexities that are sometimes associated with some trusts. Anthony Nixon, partner at solicitors Irwin Mitchell, says this is particularly appealing to anyone who has amassed their fortune from running their own business.

Anthony says: “Interest in FICs often comes from people who have built up their own business and have been using a company structure for decades. They are used to the idea of a company and they retain control.”

Anthony adds that in comparison, trusts are sometimes seen as outdated because of the loss of control of assets, and can be difficult to deal with. Some have their own inheritance tax regimes and can be complex and costly, depending on requirements.

Things to considerSetting up a FIC is not without costs. The family will likely need a solicitor to help set up the bespoke articles of association since these require careful planning. The company founder needs to be certain about how they want the wealth to be distributed and ensure that they understand their entitlements, for example, who has voting rights and whether everyone has an equal share of capital.

Anthony says: “You need to have a carefully thought out plan of what the founder wants the children to have.”

An accountant will also be required, because the company must file accounts every year and there may be a need for tax advice regarding the best way to set up and manage it, while a financial planner could be required to help with any investments and guide financial decisions. Certain investments, eg, capital gains producing, may not be tax efficient held in a corporate wrapper, although there may be good commercial reasons for doing so.

However, Emma says that expenses incurred by the FIC in managing its investments and running its business will be eligible for corporation tax relief.

She says: “This will include investment managers’ fees and remuneration paid to employees and directors. By contrast, an individual investor cannot obtain tax relief on the expenses of managing their share portfolio.”

Employees may include those from previous business that have been rolled into the FIC, or family members may wish to hire accountants, administrators or other support staff to help run the FIC.

FICs are a practical and relatively straightforward way to achieve tax-efficient succession planning of wealth, although, says Emma: “Bespoke advice is required to consider all of the family’s circumstances and intentions”. However, the costs need to be weighed against the benefits, and since not all assets are treated equally for IHT and CGT purposes, families need to think about what they own and how best this can be bequeathed.

Most importantly, individuals need to remember that the tax rules change, as do personal circumstances. It can be hard to unravel a FIC without incurring costs. Estate planning needs to be done carefully and should be kept under review.

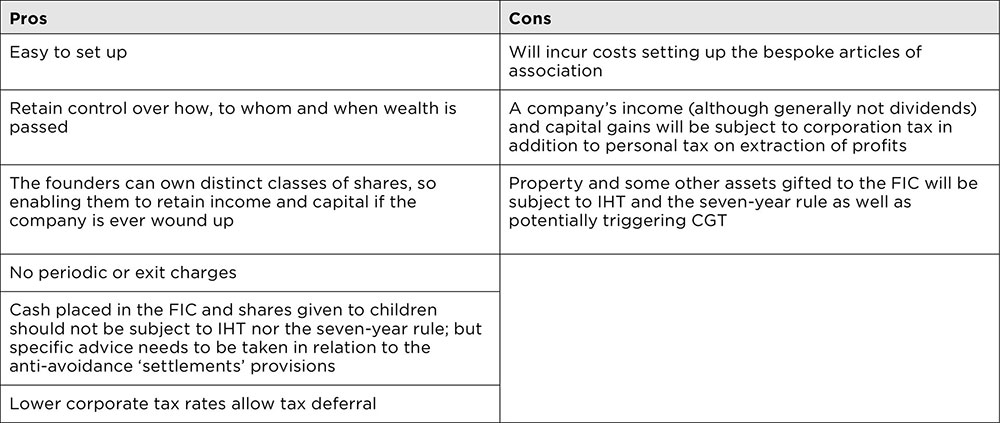

The pros and cons of FICs Seen a blog, news story or discussion online that you think might interest CISI members? Email bethan.rees@wardour.co.uk.

Seen a blog, news story or discussion online that you think might interest CISI members? Email bethan.rees@wardour.co.uk.