Funding is currently falling short when it comes to facilitating ambitious 2030 ‘Agenda for Sustainable Development’ targets. But are innovative approaches such as ‘blended finance’ providing cause for optimism, and opportunities for investors?

by Milena Bellow

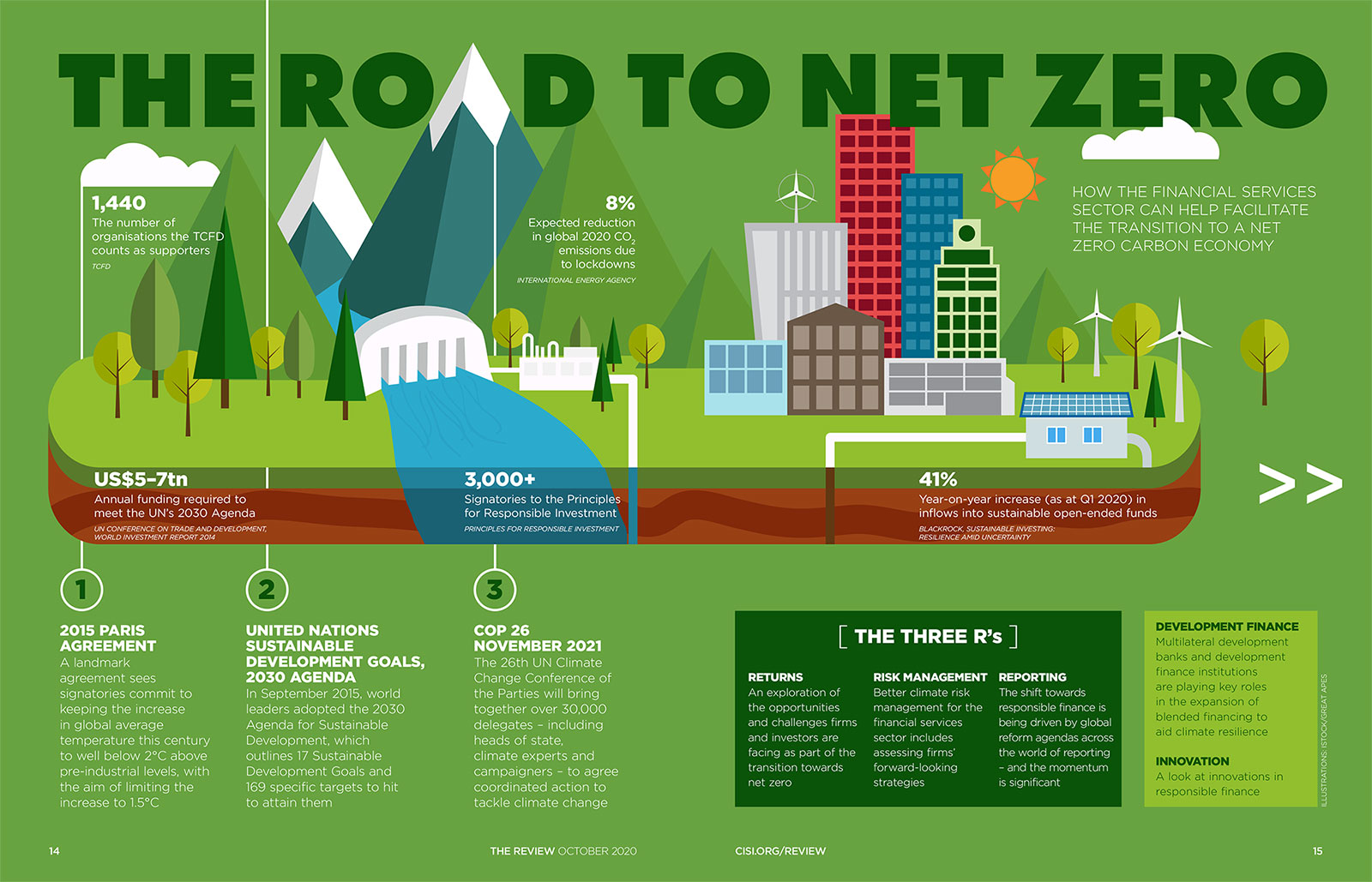

Fulfilling the aims of the United Nations 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development and the 2015 Paris Agreement will require significant funding. If the international community is to meet the 2030 Agenda, which includes the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), then between US$5tn and US$7tn per year is required. This far outstrips current public and private investment in SDG-related sectors in developing countries, with the funding gap per year standing at US$2.5tn, according to the World investment report 2014 by the UN Conference on Trade and Development.

Bridging the gapHow to bridge such a huge gap? Blended financing could be the answer. It could encourage implementation of the SDGs by aligning private sector incentives with public sector goals.

Concessional loans and non-concessional resources are used to attract additional capital, with private investors offered a first-loss guarantee (a form of credit enhancement where a third party agrees to indemnify holders for a given amount or percentage of any losses from the asset pool), mezzanine (a hybrid form of financing that sits between traditional debt and equity) or senior debt (debt and obligations which must be repaid first in the case of bankruptcy) to mitigate the risk, and public sector or development institutions shouldering initial losses.

"The EBRD set a target to sign at least 40% of its annual business in green investments by 2020, which it has reached and exceeded"

Multilateral development banks (MDBs) and development finance institutions (DFIs) can play a significant role in the deployment of blended finance, particularly in emerging and frontier economies. MDBs – such as the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD) and the Islamic Development Bank (IsDB) – are international financial institutions chartered by two or more countries to encourage development in poorer nations, usually by providing loans and grants to members. DFIs (such as the African Development Bank) specialise in promoting development and are usually majority-owned by national governments.

Other options

Another option is donor-advised funds (DAFs), which can help facilitate private investment in charitable causes. DAFs are administered by a third party; the donor makes their contribution, advises as to the charitable cause they would like the contribution to benefit, and the administrator then conducts due diligence and distributes the money.

According to a Refinitiv podcast discussing DAFs as potential sources for social impact investment, DAFs had more than US$100bn in assets as at May 2020. In the podcast Rick Davis, managing partner at LOHAS Advisors, says that DAFs are “ideal for investing in healthcare”, a particularly pertinent topic in light of the Covid-19 crisis. As the funds in DAFs have already been donated, he points out that they are not affected by stock market fluctuations or economic downturns.

The EBRDThe EBRD is active in 37 countries and was the first MDB to have an explicit environmental mandate in its charter.

Blended finance has become an important area for the EBRD, says Alan Rousso, managing director for external relations and partnerships at the bank: "The EBRD set a target to sign at least 40% of its annual business in green investments by 2020, which it has reached and exceeded." Thus far, the EBRD has financed more than 1,900 green projects, and these are expected to reduce carbon emissions by 102 million tonnes per year.

The Islamic Development BankThe IsDB provides Islamic financing in accordance with Shariah law. Islamic financing lends itself well to responsible financing, as many of its key tenets have responsibility built in: usury, excessive risk and uncertainty must be avoided, and risk is shared between financial institutions and those who use them, encouraging longer-term relationships. An element of stewardship is therefore brought into the relationship between institutions providing Islamic finance and their clients. According to the Islamic finance development report 2019, published by the Islamic Corporation for the Development of the Private Sector and Refinitiv, total Islamic finance assets in 2018 were US$2.5tn, up from US$2.4tn in 2017. This is clearly a growth area, and the IsDB is well positioned to lead the way.

Belt and Road InitiativeChina’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), established in 2013, is an enormous infrastructure project that could reach up to 70% of the world’s population. It was not initially developed with the SDGs in mind, but in 2016 the Chinese government proposed a ‘green’ BRI.

According to China’s Belt and Road by Yu, Rizzi, Tettamanti, Ziccardi and Guo (2018), 90% of BRI infrastructure investment in Asia comes from the public sector. Further private-sector investment is needed. To that end the Chinese government has set up a multilateral development financing cooperation centre with eight multilateral development institutions and has introduced a debt sustainability analysis framework.

DownsidesCritics point to some of the drawbacks of blended finance as deployed by MDBs and DFIs. The Overseas Development Institute (ODI), a London-based think tank, says that blended financing projects frequently overlook the countries that need the most help. MDBs and DFIs must maintain their credit ratings, and investors looking to make a profit often don’t want to invest in countries with low – or no – credit ratings. According to its 2019 Blended finance in the poorest countries report, the ODI estimates that every US$1 of MDB and DFI invested mobilises, on average, just US$0.37 of private financing for low-income countries (LICs).

"The Covid-19 pandemic has served to highlight that we are only as strong as the most vulnerable members of society"

One of the key obstacles to creating long-term financing solutions that will actually bring about the necessary climate change mitigation efforts, says Michael Mainelli, Chartered FCSI(Hon), chair of think tank Z/Yen and Sheriff of the City of London 2019–20, is government. Dependent on the electoral cycle, governments think short term. So how can private investors have confidence that a project or technology they invest in because of government policy and subsidies won’t be scrapped as soon as the political wind changes? His answer: environmental policy performance bonds. The interest rates on these bonds would be linked to CO2 reduction targets.

Towards a responsible futureSDG projects are facing unexpected Covid-19-induced pressures. Funding and investment need to expand, but the effects of the pandemic have moved activity in the opposite direction. Kristalina Georgieva, managing director of the International Monetary Fund, stated in April 2020 that since the start of the pandemic, “nearly US$90bn” has left emerging and developing markets.

The Covid-19 pandemic has served to highlight that we are only as strong as the most vulnerable members of society. Funding the SDGs is more important than ever, in order to create healthy, thriving communities. Blended finance offers opportunities to scale responses to the SDGs on a truly global basis, but we should be wary of assuming that the funding gap will be closed solely through the use of ever-greater amounts of blended financing. As Alan says, “blended finance can make an important contribution to closing the SDGs funding gap, but it is not a silver bullet.”

Click to enlarge

Click to enlarge

The full article was originally published in the October 2020 flipbook edition of The Review.

The full flipbook edition is now available online for all members.