Elliot Jones, former analyst at the Bank of England and founder of Exploring Happiness, tells us how we can measure our happiness, and why it might be connected to economics

by Bethan Rees

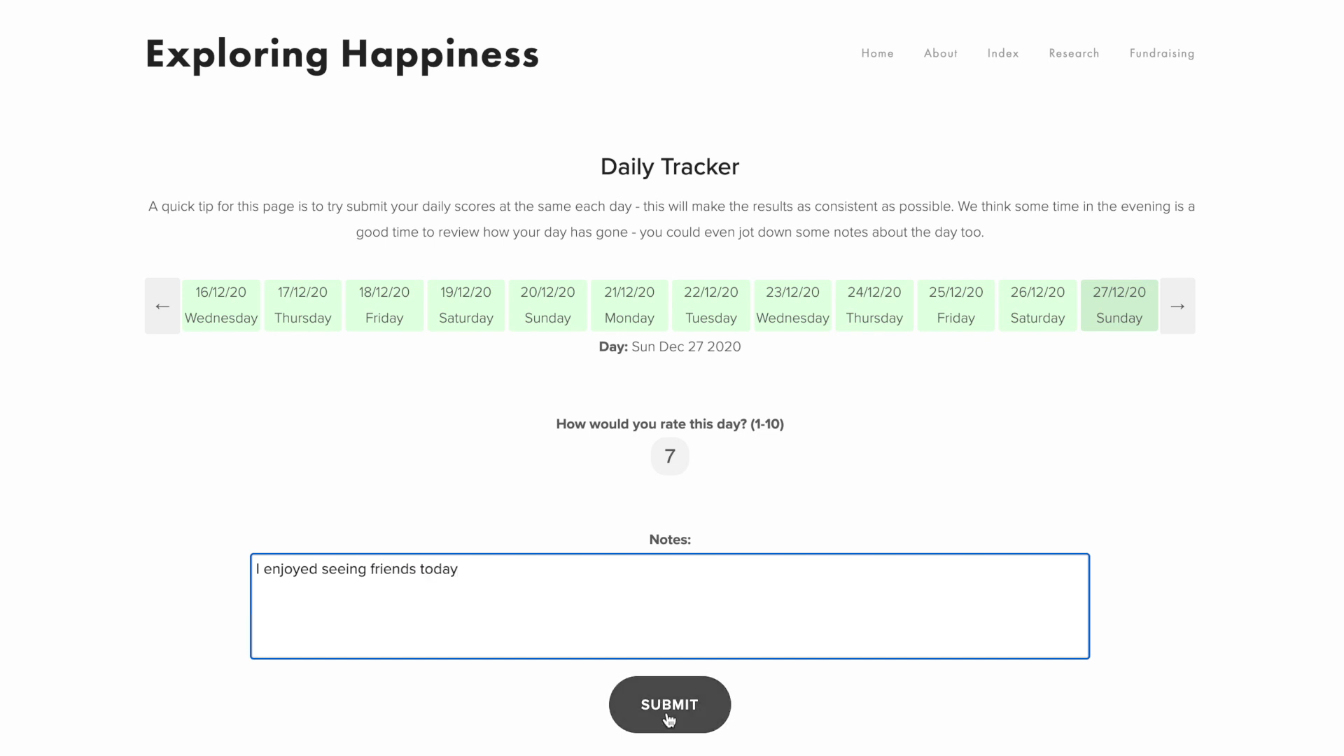

Exploring Happiness (EH) is an organisation that produces research that generates policy recommendations towards increasing “happiness and wellbeing in society in a sustainable and equal way”, according to its site. EH has created an index so users can track their happiness over a period of time.

We speak to Elliot Jones about how happiness can be measured, how Covid-19 has impacted this, and why social media and the spread of misinformation could be contributing to unhappiness.

What motivated you to start EH?

I read Happiness: lessons from a new science by the London School of Economics Professor Richard Layard in 2016 and it really opened my eyes as to how we should think about progress. I find happiness research interesting at both the individual level and the policy level. It’s a relatively new area of research, such that I am confident that we can make meaningful contributions to the evidence base. In my view, policymaking can often be quite narrow in its focus. By considering happiness, wellbeing and sustainability, the way we structure things could be quite different from how they are today. Beyond our research, Exploring Happiness was also started to make tangible differences to people’s lives in the here and now, through our fundraising efforts and Happiness Index.

How would you define happiness economics?

We define it as the study of increasing happiness and wellbeing in society in a sustainable and equal way. This is consistent with our core objective. When we launched EH in January 2019, we hadn’t included the word ‘equal’ in our definition. However, as we have completed further research, we now consider the distribution of happiness to be at least as important as the average across a population. The distribution varies widely both within and among countries.

How does the Exploring Happiness Index work?

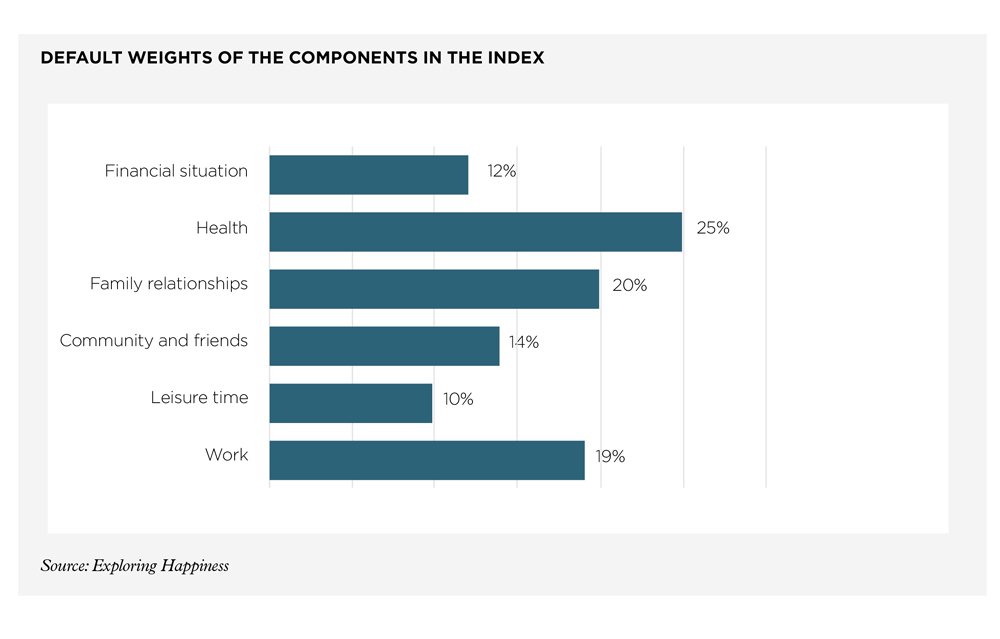

It is made up of a number of components that have been identified as key determinants of life satisfaction, for example, health, work, and relationships. The amount to which they contribute towards life satisfaction determines their default weight (health, for example, is shown to have a bigger impact on life satisfaction than income in The origins of Happiness by Andrew E Clark, Sarah Flèche, Richard Layard, Nattavudh Powdthavee and George Ward, so the starting weight for health is larger).

The components within a user’s index will be slightly different, depending on their current circumstances. When a user signs up, they are presented with 13 different ‘individual types’ to choose from, such as an employed worker, student or parent/carer. Then, out of index choices that include components such as ‘family relationships’, ‘community and friends’, users are able to choose the level of importance of each (low, medium, high or N/A), and the corresponding weights will shift a little to reflect these choices. In this way, we look to make the index unique to each user.

The Q1 2020 EH research article states that countries with higher government revenues and expenditure, as a proportion of GDP, tend to report higher wellbeing scores. Why is this?

In this article, we outline the correlations that currently exist between these variables, but we don’t suggest these are causal relationships. However, our article does provide some interesting insights. We have two samples: one containing 146 countries, another is a subset of 23 richer countries. The correlation is stronger in the larger sample, but positive in both. This is because richer countries report both higher wellbeing scores and are able to extract larger amounts of tax (and therefore spend more), than less rich countries. In short, each variable is impacted by an income effect. We use our rich country sub-sample to remove this effect, allowing for more consistent comparison across countries.

A number of the countries that score the highest in the UN World happiness report 2020 (ie, the Nordics) also have higher than average tax revenues and government spending. This provided motivation for our analysis, as we looked to test if this relationship holds for a large sample of countries. Previous studies have also identified that higher unemployment benefits and more broadly, increases in government spending, are associated with higher wellbeing. Of course, what is likely to matter much more is how governments spend, rather than how much.

The Q3 2020 EH research article says that "little attention is paid towards" the economic impact of Covid-19 on wellbeing. What are the other impacts of the pandemic on our happiness, and why have these been looked over?

The ONS personal wellbeing measures have proved insightful. In the first UK lockdown we observed sharp deteriorations in measures of happiness and increased anxiety. These have gradually recovered as we have become accustomed to lockdown life, but remain worse than historical averages. The opposite has been true for measures of life satisfaction and our sense of worth, which have steadily declined since the pandemic began.

Government restrictions have made maintaining relationships with family, friends and work colleagues more difficult. The uncertainty has worsened our mental health (see previous Review article on mental health in a pandemic), and while a number of us have more leisure time, we can’t always use it how we would like to.

It’s likely that these effects have been overlooked because of both past experience and the complications that these social effects raise. We know how to respond to financial shocks, and we are able to do so relatively effectively in a short amount of time. The social effects blur the clarity of the situation, as they make a case for going against the required policy direction to manage the pandemic.

The Q3 2020 report says that the analysis "could lead you to conclude that the impact of the pandemic on wellbeing through financial channels has been (or is likely to be) small". What do you think the likely impact on wellbeing through financial channels will be?

The financial wellbeing impact of the pandemic on some sections of society, particularly young people and those on lower incomes, has been significant. I don’t want to give the impression that we were suggesting otherwise. Fortunately, government policy support, such as the job retention scheme, has helped here, but we should be most concerned with what the permanent effects of this crisis will be (ie, the jobs and businesses that will not recover). To manage the impact of this on wellbeing, government support for those out of work should remain generous, and good availability of job retraining is also important.

I think the main reason for the inconsistency is the lack of awareness of the relationship between income and happiness. As we outline in our index methodology, previous studies, such as that in The origins of Happiness, have identified that only about 2% of the variation in happiness can be explained by income. It is important to remember that this is an average across a large sample of people, and for some groups income is much more important than others. But once you consider this relationship across the whole population, it doesn’t come as a surprise to see there are bigger influences on our wellbeing during the pandemic.

The Q3 2020 report says that the misinformation and scaremongering in the media and on social media increases anxiety for citizens and drives polarisation between them. What are some ways that this can be improved upon?

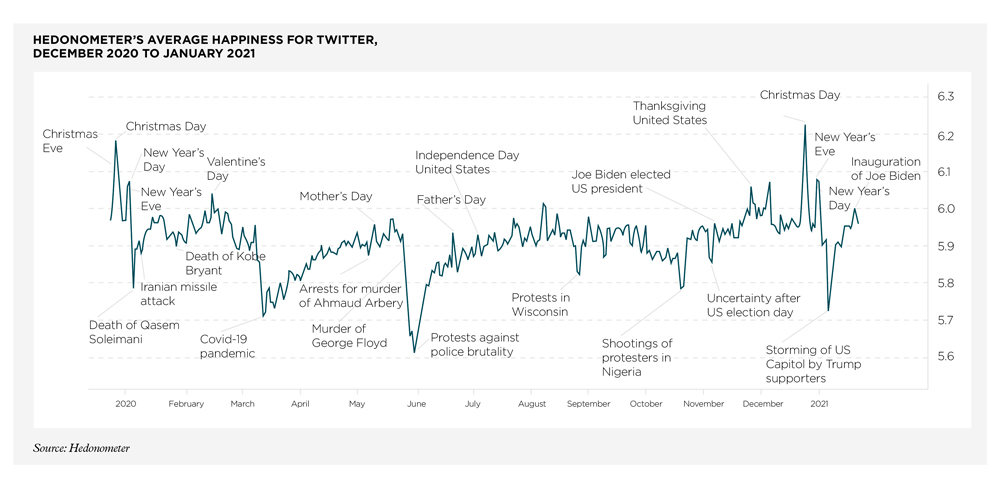

Time spent online has increased during the pandemic. Researchers are now able to gain insights into our emotions through tracking data on social media platforms, and have developed measures that match well against significant events. The Hedonometer (see below) has merged 5,000 of the most frequent words from Google Books, New York Times articles, music lyrics and Twitter messages resulting in a set of roughly 10,000 unique words, which are scored on a nine point scale of happiness (one being sad and nine being happy).

Some studies highlight how social media may be negatively affecting us, through increased social comparisons, which create unrealistic expectations, leading to lower self-esteem. In addition, increasing political polarisation doesn’t help matters.

Some studies highlight how social media may be negatively affecting us, through increased social comparisons, which create unrealistic expectations, leading to lower self-esteem. In addition, increasing political polarisation doesn’t help matters.

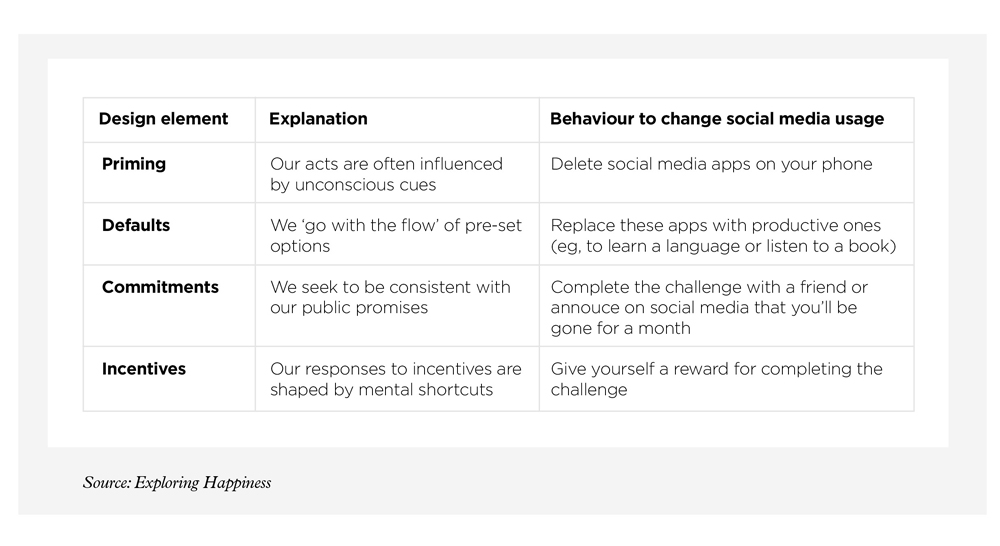

To deal with misinformation, our tips would be to think critically about what you are reading, try not to form judgements too quickly and try to consider more than one perspective. For social media, perhaps consider a digital detox for one month. The table below draws from what behavioural science can teach us about changing behaviour.

In the table below, the first two columns are taken from behavioural scientist Paul Dolan's book Happiness by design and I have applied this framework in the third column, showing how you could reduce social media usage.

In the Q2 2020 report, one of the policy recommendations concerns climate change. How are climate change and happiness connected?

Almost all of our policy recommendations in this report touched on climate in some way, as we put together our proposals for a green recovery. Our view is that currently there is no greater pressing policy issue than climate change. The link here is simply that any increase in happiness that significantly damages the environment cannot be sustainable and will therefore have a negative impact on the happiness of future generations. This is why our core objective is to increase happiness and wellbeing in society in a sustainable way.

What role does community life play in happiness? And how can we keep the momentum of the 'rainbow effect' going post-Covid-19?

When our communities work well they make us feel safe and needed. Trust plays an important role, as societies with high levels of trust have a positive association with happiness. In order to keep the momentum up, I think we need to be a bit creative, because I don’t think communities will naturally maintain a level of togetherness once things normalise. Some of the most common small-scale ideas include setting up ways to share with your neighbours, since they come with some economic benefits too. For example, exchanging vegetables grown in gardens, or setting up programmes to share books or tools.

On a larger scale, greater public investment is needed to support the charity sector and to build social infrastructure. Charities help those that benefit the most from a greater community spirit. Recent analysis has highlighted that charities are facing serious financial challenges during a period of heightened need for their services.

Does consumer spending relate to happiness? And has the Covid-19 pandemic impacted this if so?

There is a relationship between consumer spending and happiness, but it matters how we consume. The evidence suggests that relative to purchases of material possessions for ourselves, purchases for others or experiential purchases, for example eating out, travel, or entertainment, generate greater happiness. This suggests retail therapy is not likely to be that helpful. The pandemic has had a big impact on both experiential purchases and in-store retail spending, while online retail spending has increased significantly. I expect that the lack of money spent on experiences over the past 12 months will have had a bigger effect on happiness than the lack of time spent shopping for more stuff that we probably don’t need.

Why aren't policymakers placing more emphasis on happiness? What more can be done?

I think changing the status quo is hard and social progress tends to be slow, meaning it will take some time for this to come further into the centre stage. However, there is evidence that some governments are listening. A few countries such as

New Zealand,

Iceland and

Scotland – which, incidentally, are all run by women – have adopted wellbeing as their overarching goal, while many other countries now use wellbeing as a key measure of success.

About the expert

Elliot Jones is a former analyst at the Bank of England and founder of Exploring Happiness, which produces research generating policy recommendations towards increasing happiness and wellbeing in society.

He's recently moved to New Zealand, which has adopted wellbeing as an overarching goal.

He will continue working in the financial services sector.

In terms of what more can be done, I think the cost argument is very persuasive. Although our core objective is increasing happiness, typically more focus is put towards reducing misery at both EH and other institutions. This means a greater focus on treating mental illnesses. A January 2020 Deloitte report estimates that the cost of poor mental health to UK employers in the private sector each year is £42-45bn. This means significant investment in psychological therapies for mental illnesses would both pay for themselves and increase happiness.

Lastly, what makes you happy?

It certainly helps that I am aware of how lucky I am. I know that as a white male with a middle-class background from one of the richest countries in the world, I almost couldn’t be more privileged. Of course, I try to use this as a means of making a difference, which perhaps ironically, is good for my own happiness. There's a lot to say about the selfishness of selflessness. But more broadly, I think I stay happy by keeping things light-hearted. My view tends to be simply to separate what we can and can't control: do the best with what we can control and don’t worry too much about the rest. Otherwise, I think I am happiest either on holiday or in the pub with my friends. Hopefully both will be possible soon enough.