A cryptocurrency operates independently of a central bank and uses an encrypted digital currency to regulate units and verification of fund transfers. The first cryptocurrency, bitcoin, was created less than ten years ago.

Now there are millions of unique active users of cryptocurrency wallets, according to estimates from the University of Cambridge Judge Business School’s

Global cryptocurrency benchmarking study, meaning governance and regulation is on the horizon.

What are MDLs? Mutual Distributed Ledger (MDL) systems (blockchains) are multi-organisational databases with a super audit trail following a set of rules. To date, the most popular MDL application has been cryptocurrencies, with their associated initial coin offerings (ICOs).

What are the main governance challenges around the ownership and regulation of cryptocurrencies? Governance structures have had a low priority so far, but trust in these increasingly popular systems depends on incorporating good governance principles, so interest has been rising in ensuring good governance.

Some basic governance questions apply to all MDLs:

- How do you go about creating and enforcing the rules by which the MDL is run?

- What happens when there are disputes between users?

- Who is allowed to change the software the ledger runs on, and who should have access to the data it contains?

- How do you go about managing risk and performance?

How should governance structures for cryptocurrencies be organised? Effective governance in MDL systems rests on three pillars:

- Architecture: the role of the governance structure, its composition, remit, powers, responsibilities and its relationship with users is a critical component.

- Accountability: effective governance of MDLs enhances trust. Trust is enhanced when a governance structure is accountable to its stakeholders, transparent in its decision-making and subject to periodic audit and third-party review.

- Action: the governance structure must develop strategic and risk management plans, which are delivered through effective performance management frameworks. Trust can be further enhanced through the use of the voluntary standards market to independently verify performance metrics and the systems established to compile them.

How does governance differ for public, state-sponsored and private MDLs and cryptocurrencies?There are many different classes of MDL, and more emerging. Three seem important.

Public, unowned MDLs are struggling to build complex systems without human governance. MDLs are finding that certain functions, particularly software upgrades, need some central guidance.

I know of no state-sponsored cryptocurrencies … yet.

Private MDLs are interesting because, outside of cryptocurrencies, they are where the action is. Private MDLs are also realising that multi-organisational governance needs care and attention if you want a corporation to work together on an MDL.

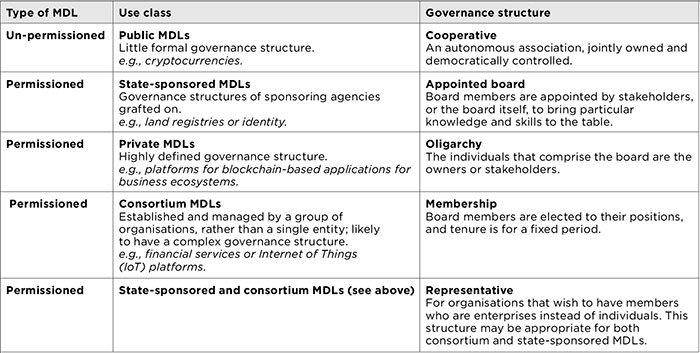

Table 1 summarises the MDLs and governance structures we have found.

Table 1: MDL use classes and their corresponding governance structures

Source: Responsibility without power? The governance of Mutual Distributed Ledgers.

How are rules created for cryptocurrency ledgers, and who oversees their application?

Source: Responsibility without power? The governance of Mutual Distributed Ledgers.

How are rules created for cryptocurrency ledgers, and who oversees their application? As before, cryptocurrencies are a special type of MDL. Their rules are written by their initial programmers. No single person or body oversees the application.

Aside from hacking and cyber attacks, two high-profile governance incidents illustrate some of the problems – the 2016 ‘fork’ (permanent divergence from the previous version of the protocol software, requiring all users to upgrade, and invalidating transactions from old nodes that have not been upgraded) of Ethereum – a distributed public blockchain network that features smart contract functionality – and the 2017 fork of the Bitcoin MDL.

In June 2016, 3.6m ether (cryptcurrency used on the Ethereum blockchain – worth around $70m at the time) was drained from the decentralised autonomous organisation (DAO) account by a hacker. In July 2016, 89% of ether miners voted to refund the money and alter the ledger accordingly.

The 2017 fork of Bitcoin took place in order to increase some seriously constrained transactions throughput (a few hundred thousand transactions per day compared with perhaps 20,000–40,000 transactions per second by major credit card systems at peak periods). This change required a majority of nodes (circa 7,000 in total) to agree to upgrade their software. Minority groups objected, leading to a schism.

More incidents of confusion and scandal lie ahead, but most MDLs will wind up with some formal governance structure

In both cases, a majority of users decided to change the rules of the system post facto, and people were struggling to resolve an ethical or performance governance issue. Minorities of ether and bitcoin users kept a separate ledger going forward: Ethereum Classic and Bitcash respectively.

Tempers were high in both situations, but by ‘solving the problem’ the majority overruled their own code. ‘Tyranny of the code’ transformed into ‘tyranny of the majority’. What if, in future, the majority decide to reverse transactions to do with tobacco or fur, or a country with a brash president, or anything to do with historic statutes?

Cryptocurrencies are, in many ways, experiments to test the limits of removing central control. What we seem to be finding in practice is that human intervention is still needed for practical applications.

What happens in the case of a dispute, and who is allowed to change the software application? There are two types of dispute: a local dispute about specific transactions; and a system-wide dispute about actions objectionable to the majority, upgrades or the money-supply algorithm.

Specific dispute transactions might be handled more sensibly by code in the future. For example, perhaps there is dispute resolution insurance where a ‘jury’ of fellow cryptocurrency holders are paid to resolve a transactional dispute.

Software upgrades or changes to the money-supply algorithm may require human intervention, such as the creation of a board, to make such decisions.

About the expert

Professor Michael Mainelli FCCA FCSI FBCS is executive chairman at Z/Yen Group.

He began his career as a research scientist in aerospace and cartography. He entered the City of London in 1984 ahead of the ‘Big Bang’. During a spell in merchant banking, he co-founded Z/Yen in 1994 to promote societal advance through better finance and technology.

His third book, The price of fish: a new approach to wicked economics and better decisions, won the 2012 Independent Publisher Book Awards’ Finance, Investment & Economics Gold Prize.

Bitcoin has tried to backward-integrate a ‘foundation’, but this is difficult as the software has already been released. Ethereum began with a foundation, but it was founded with too little control to dictate future direction on its own.

Future cryptocurrencies are likely to pay more attention to where human intervention is needed, and establish appropriate structures from the beginning. We are all learning.

What is the future of governance and cryptocurrencies?The tools for effective governance of MDLs are not that different from those used for the governance of other multi-organisational structures.

More incidents of confusion and scandal lie ahead, but most MDLs will wind up with some formal governance structure. Future formal governance structures are likely to blend today’s multi-organisational approaches with a stronger reliance on technology, automating away basic governance issues.

Within MDL technology lies the seeds for automating the resolution of many disputes. So-called ‘smart contracts’ – embedded pieces of code within the ledger – permit complex resolution scenarios using software. When these fail, the software can invoke human intervention.

As ever, to solve a problem you first have to recognise you have one. Increasingly, MDLs and cryptocurrencies recognise that there are limits to ‘no human intervention’. They are there to solve human problems. However, humans will be part of the solution and new governance systems will aim to include humans appropriately.