Private investors have usually found sanctuary in equities, bonds and cash. Although multi-asset funds have veered into offering more choice, most investors in the UK favour tried and tested ways of putting their money to work. This is typified by the ISA split in the country, according to the Office for National Statistics (ONS). The number of ISA accounts subscribed to each year has consistently been around or over 12 million since the start of the century. For the 2015–16 year, around £80bn was subscribed to adult ISAs, with almost 75% of this in cash. So there is no great swell, yet, of investors opting for more esoteric investments.

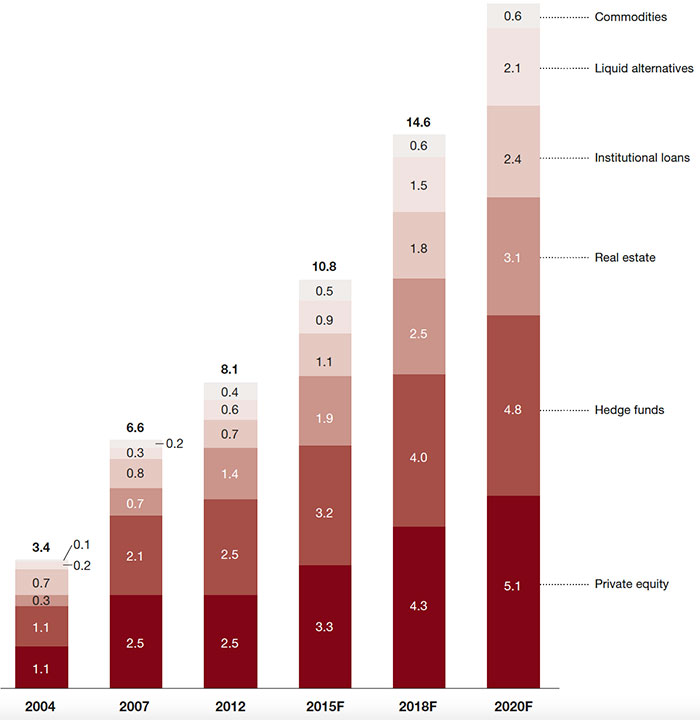

But increasingly, there are wider opportunities. Investing in alternative assets – investments not traded on stock markets – such as private equity, infrastructure, property, commodities, hedge funds and various forms of debt are becoming more accessible. A PwC report estimates that the overall market for alternatives (through funds, exchange-traded funds and direct) will almost double between 2015 and 2020: from $10tn in assets to $18.1tn (see Graph 1). Some of this growth is driven by need: the paltry returns from cash are not improving, and extra sources of portfolio diversification are often welcome.

Graph 1: Global alternative assets (US$ in trillions) by asset class

Source: Alternative investments: It's time to pay attention, Strategy& and PwC (2015)

Source: Alternative investments: It's time to pay attention, Strategy& and PwC (2015)

As well as access, issues around liquidity have typically permeated the alternative assets class. If you have the ready capital it’s easy to invest in property directly, but you can’t get hold of your funds in a hurry if you need to sell that property. So one of the most uncomplicated (and efficient) ways for private investors to gain access to alternative assets is through a closed-ended investment company – also known as an investment trust.

Investment companiesInvestment companies provide fluid access to alternatives as they are companies in their own right, listed on the stock exchange, with their shares easily bought and sold. They can make direct investments in unlisted companies and large infrastructure projects. Investing in infrastructure, for example, would often mean prohibitive entry requirements for ordinary investors, perhaps £1m or more.

Figures from the Association of Investment Companies (AIC), released in June 2017, reveal that investment trust purchases by financial advisers and wealth managers hit an all-time high of £777m in the year ending 31 March 2017. That’s 11% up on 2015. Trust purchases for Q1 2017 were up 85% on the year and 25% on the previous quarter.

“The benefit of an investment company is that you can invest in more illiquid assets within a liquid vehicle,” says the head of training at the AIC, Nick Britton. Whereas with an open-ended fund, a certain amount of investment has to be held in cash, investment companies can get much more exposure to an asset. This can produce decent long-term rewards. Closed-ended property funds, for example, have produced a total return of 48% over ten years, says Nick, while their open-ended counterparts have managed around 20%.

Advances in energy storage could provide interesting opportunities for investors

The government’s

National infrastructure delivery plan 2016–2021 could offer attractive potential for investors in infrastructure. An event co-hosted by the professional accountancy association ACCA UK and the CISI in 2016 explored the opportunities and challenges that the sector faces (see ‘

Infrastructure investment: the risks and benefits to investors’). The forum stated that government spending on infrastructure dropped from 11.5% of GDP in the 1970s to 3.5% of GDP today, but public sector net debt has hit £1.6tn. So there is little appetite for the government to get mired in further debt.

Increasingly, it is hoped the private sector will help fund infrastructure projects. In fact, the government’s proposed plans – for £483bn of investment in over 600 infrastructure projects – needs more than half of the funding for these projects to come from the private sector.

Sectors with potentialIain Scouller, a managing director with Stifel Funds, believes the scale of upcoming projects represents good potential for investors. “At the moment, we are seeing particular interest in funds that give a good yield,” he says, citing renewable and infrastructure investment companies as two examples that may provide robust long-term potential.

It is this yield that is indeed attractive. The CISI/ ACCA event highlighted that infrastructure is appealing to institutional investors as yields generally exceed those of both 20-year gilts and FTSE 100 companies, with 4–7% returns from yielding infrastructure assets. Equally, investors pursuing capital gains from assets yet to be built (known as ‘greenfield’ assets) could anticipate returns of 8%–12%. As an added benefit, the infrastructure sector is also attractive because it provides index-linked returns that do not correlate to volatility in the stock market. As Nick states: “There is little relationship between the fortunes of quoted companies and the government- backed income streams from the contract to maintain a motorway or build a hospital.”

Iain also has faith in the potential for renewables. According to the Department for Business, Energy & Industrial Strategy, renewables’ share of UK electricity generation was 25% in the third quarter of 2016. This is a tremendous increase from the 3% when the first wind turbines cranked into action in 2003 off the coast of north Wales. In particular, Iain thinks the advances in energy storage could provide interesting opportunities for investors who choose investment companies that target this area.

Uncorrelated performance

Investment trends come and go, however, so should we think that investing in alternatives could go the way of sub-prime mortgage bundles? Robbie Robertson, head of investment companies at Canaccord Genuity, doesn’t think so. “We don’t believe that demand for alternatives is cyclical, we think it is secular. People were very disappointed with the performance of equities in 2008, and since then we have seen a more general surge for forms of income which are more stable.”

Again, the demand for assets uncorrelated to equities is notable. Robbie cites 2008 as a watershed for alternative asset investing, not just for the events of that year, but for the frustration with events such as the technology boom and bust before that also coming to a head.

This frustration heralded the growth of infrastructure investment companies such as HICL and John Laing Infrastructure, among others. “They really changed the way the sector was viewed,” says Robbie, “delivering not just uncorrelated returns, but an interesting yield.”

Private equity

So what about private equity investing for retail clients? Historically, institutional investors and high-net-worth individuals usually provided the capital for private equity. This money was then used to help an unlisted company to develop quickly – whether by making an acquisition, investing in new technology or by boosting working capital or its balance sheet. Returns are often high to compensate for the extra risk.

The sector is still recovering reputationally, however, after a number of private equity firms (notably Candover) were badly hit from the fallout of the financial crisis. Many firms had been extremely highly geared and could not cope with elevated debt levels as the economy soured. Robbie believes there are still good private equity companies out there. “More are coming back to private equity,” he says. “Many of the issues they faced are a decade old. We’re seeing portfolios of very high quality and companies with fantastic management.”

In fact, the sector appears to be thriving. According to a 2017 report by leading alternatives data provider Preqin, private equity assets under management hit an all-time high in 2016 at $2.49tn – with investors no doubt attracted to annualised returns of 16.4% in the three years to June 2016.

Robbie also points to numerous other interesting opportunities in the alternative asset space: social infrastructure funds for those seeking inflation-proofed income, niche property sectors such as student property and doctor surgery estates, peer-to-peer lending opportunities and specialist debt.

Volatility and liquidity

As with all investing, there are traditional concerns surrounding the investment potential of certain alternative assets. Yet Iain believes that by taking the investment company route you at least negate some of the concerns around volatility and liquidity. “Compared to other listed companies, volatility is much less than the mainstream. And because you don’t own the assets directly, liquidity is also not an issue, especially when some of these companies are worth billions.”

Of course, you don’t have to go the investment company route. Open-ended investment companies also invest in property, and indirectly in infrastructure and private equity. But these funds do have to deal with the “inefficiencies of managing inflows and outflows, which are often sentiment driven and usually at the wrong point in the cycle,” says a report on property investment by Canaccord Genuity.

Access, liquidity and volatility have traditionally been barriers to the alternative investment world for mainstream retail investors. The shared risk of investment trusts, which are becoming increasingly popular, mean wealth managers can give a wider group of clients exposure to this higher-return environment, creating a more diversified portfolio for them.

In the print version of this article in the Q3 edition of The Review, Nick Britton, head of training at the Association of Investment Companies, is incorrectly quoted as saying: “The benefit of an investment company is that you can get access to government guaranteed schemes, which often produce steady returns over many years.” Nick was referring to infrastructure investment companies, not investment companies in general. In addition, he spoke of “government-backed contracts”, not “government guaranteed schemes”.

In addition, HICL and John Laing are incorrectly described in the print version as "property investment companies" instead of infrastructure investment companies.

Nick provided an alternative quote for this online version of the article. The CISI apologises for the errors.