Having bounced back from the financial crisis faster than their European rivals, US investment banks remain well placed to widen their lead

by Paul Golden

The 1980s could be said to mark the starting point of the modern investment banking era in the US, with derivatives, high yield and structured products having been established and an increased emphasis placed on trading rather than deal-making.

Over the following decade, the market experienced an unprecedented initial public offering boom, while the 1999 Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act repealed the Glass-Steagall Act of 1933, which had separated investment banking from commercial banking.

The faster pace of reform in the US was welcomed by the country’s investment banks, which had spent much of the previous two decades calling for deregulation.

Europeans viewed this as an American banking invasion of Europe, explains Professor Richard Sylla, Professor Emeritus of Economics and the former Henry Kaufman Professor of the History of Financial Institutions and Markets at New York University Stern School of Business.

“But the American banks didn’t feel like invaders,” he says, “more like they were escaping and had more freedom. The real story here is the weakness of the European banks. They came and operated in the US, but they never seemed to do as well as our bankers did.”

The end of the party?

It seemed like the party might have ended in 2007 when the collapse of the US sub-prime mortgage market precipitated the most damaging financial crisis since the Great Depression of the 1930s. But the actions taken over the following months and years enabled the US investment banks to reinforce their global corporate financial services market primacy.

An Oliver Wyman ‘blue paper’ published in 2019 shows that in 2012, the market share of US banks in Europe and European banks in the US was roughly the same (31% and 29% respectively). However, by 2018 the US banks had increased their European market share to 40%, while European banks saw their US market share fall to 20%

The most significant difference between the US and European response to the crisis was the Troubled Asset Relief Program which saw the US government and Federal Reserve immediately recapitalised by the US banks, whereas capital issues continued to hamper European banks.

This coincided with the exposure of the European banks to the eurozone crisis and was followed by a more severe regulatory backlash. The revised Markets in Financial Instruments Directive (MiFID II) alone has a plethora of complex requirements that have improved transparency for investors, but added to the compliance burden on banks.

Another tough year

The bad news for European financial institutions is that it has been another tough year for investment banking in Europe. In March, the chief executive of UBS referred to “one of the worst first quarter environments in recent history”. Then in July, Deutsche Bank announced a major restructuring that will reduce headcount by around 20% and cost in excess of US$8bn.

When lower GDP growth across many parts of Europe is added to the equation, it is easy to see why European banks are struggling to compete with their counterparts across the Atlantic, suggests Christian Edelmann, co-head of EMEA financial services at Oliver Wyman.

“There are also structural considerations to take into account, such as market size and profitability,” he says. “Higher profitability also enables banks to better attract and retain talent.”

Topping the table

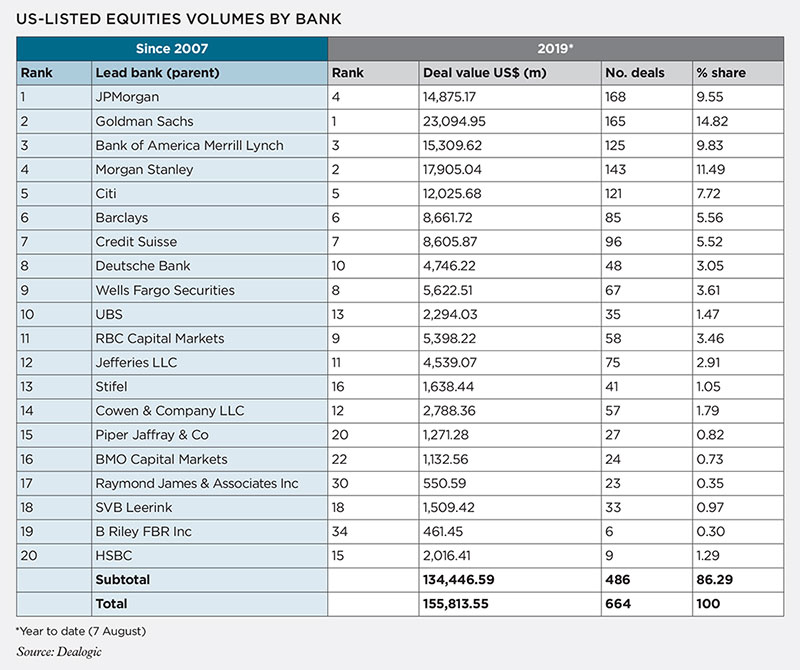

Data on US-listed equities volumes shows that the top five rated banks in 2019 are all US-based and that the deal value of the fifth largest US bank is 40% higher than that of the highest rated European bank (see table below).

Christian notes that US banks have a dollar funding advantage because commercial, corporate and retail deposits are usually the cheapest form of funding, much of which comes through a branch network that European banks don’t have on anything like the same scale in the US.

Christian notes that US banks have a dollar funding advantage because commercial, corporate and retail deposits are usually the cheapest form of funding, much of which comes through a branch network that European banks don’t have on anything like the same scale in the US.

This is important because most commodity contracts are settled in dollars and approximately 80% of trade finance transactions globally are financed in dollars.

The homogenous nature of the US also helps, despite the EU’s best efforts to promote capital markets union.

“Europe doesn’t really have a single banking market; it has a bunch of national banking markets,” says Richard. “They talk about it a lot, but there has not been a lot of action.”

If the trade disputes between the US and China and the US and Europe were to escalate, Christian posits that it could become much harder for US banks to operate across Europe.

“When the current disparity in interest rates and GDP growth in favour of the US is added to the scale and profitability of the US, it is difficult to see how the competitive position of European banks will improve in the short to medium term,” he concludes.

The full version of this article is published in the October 2019 print edition of The Review. All members, excluding student members, are eligible to receive the quarterly print edition of the magazine. Members can opt in to receive the print edition by logging in to MyCISI, clicking on My account, then clicking the Communications tab and selecting ‘Yes’.

Once you have read the print edition, keep coming back to the digital edition of The Review, which is updated regularly with news, features and comment about the Institute and the financial services sector.

Seen a blog, news story or discussion online that you think might interest CISI members? Email bethan.rees@wardour.co.uk.